A Performa e a cidade | Performa and the city

Se se pensar que acompanhar um festival numa cidade tem também a ver com conhecer a cidade (não é disso que o teatro[1] trata?) as coisas por um lado complicam-se porque há os lugares e as histórias dos lugares mas, por outro lado, tornam-se muito menos abstractas[2]. E então, acompanhar um festival específico torna-se realmente diferente de acompanhar outro qualquer. E até pode não se tornar uma maratona.

Nunca se tratando aqui de querer “situar” geograficamente a “origem” única e fixa de um conceito e de um conjunto de práticas que parecem estar a despontar de formas parecidas em vários países[3], trata-se sim de compreender algumas das interligações entre as coisas e os lugares: neste caso entre a emergência da performance art no final dos anos 50 e o contexto específico da cidade de Nova Iorque (com a emergência dos Performance Studies nos anos 70 e as experiências de dança pós moderna do Judson Church Theatre). Isto para, à luz desta breve contextualização, sermos capazes de compreender melhor a genealogia que o festival bianual PERFORMA reclama como sua (e, deste modo, ajuda a instituir).

Performance Art. Nova Iorque, anos 1960s.

Em Outono de 1959, Allan Kaprow realizou em Nova Iorque o seu famoso 18 Happenings in 6 parts onde o termo happening foi cunhado (cujo remake, da autoria de André Lepecki, integrou a programação da Performa 07).

Na altura (“early 60’s”), Greenwich Village[4] e o Soho (em grande parte devido a AIR- Artists in Residence, um apoio do governo nas rendas dos lofts a quem provasse ser artista, lofts estes que se espalhavam downtown) eram os bairros mais “alternativos”, uma espécie de “Meca dos boémios”. Havia um espírito efervescente na arena avant-garde, um clima de confiança, prazer, folia e de transgressão, em tudo ligado à época política que o mundo em geral, e a América, em particular, atravessam, com a contestação anti-guerra do Vietnam e o clima geral de optimismo e esperança numa mudança política radical (altura em que, mais do que nunca, se afirma que “o pessoal é político”).

Nos anos 1963-64 dá-se a explosão da Pop Art. A Judson Dance Theater, com as suas experiências de democratização do corpo que dança (e não é por acaso que uma das principais obras sobre este movimento faz alusão a uma dança feita com tênis[5]), e dos movimentos que podem ser considerados dança (são desta época experiências como as roofdances de Trisha Brown, ou a entrada na dança das tasks, movimentos de tarefas quotidianas, de Yvonne Rainer,) está no seu apogeu. O Judson Poet’s TheaterLiving Theater estava no seu tempo áureo. Andy Warhol começou a fazer filmes pop, Kenneth Anger, o seu Scorpio Rising, e Jack Smith com Flaming Creatures (filmes que numa sociedade democrática vão enfrentar a censura e ser apresentados inúmeras vezes à rebeldia, porque banidos do circuito autorizado). ganhara 5 Obie awards (a honra feita ao teatro Off-Broadway do jornal iconográfico da cena avant-garde, o Village Voice). O

É também então que o Fluxus chega a Nova Iorque, e Charlotte Moorman organiza o primeiro festival de avant-garde. Como nos diz Sally Banes, expectativas crescentes começam a alimentar as mudanças sociais e culturais, altura em que a cena artística de Greenwich Village se torna o paradigma dessa transformação, por via da arte.

Os artistas avant-garde dos anos 1960 (que podemos condensar em cerca de 150 pessoas) procuram construir uma comunidade através da arte, uma comunidade alternativa que olhava para a cultura folk e popular, e produzia estilos transgressivos, iniciando um modo de produção cooperativo, contrariando a alienação do trabalho e valores reproduzidos pela geração de artistas que os precederam, bem como do status quo sociopolítico estabelecido. De facto, não se tratava de reflectir a sociedade em que se vivia, mas de mudá-la, produzindo uma nova cultura que integra o trabalho artístico com a vida e dilui as fronteiras entre participante e observador.

O happening surge então como figura expressiva da liberdade, da espontaneidade, de uma forma radical em aliar a arte à vida, desfigurando com isso a hegemonia das galerias e museus no controle da produção e expressão artísticas. Já com Jackson Pollock, o gesto da pincelada havia-se libertado da tela, transformando a pintura em evento performativo, ao fazer da pintura uma espécie de dança expressiva em que cada gesto faz espalhar a tinta na tela (que passa a ser índice da acção), a consumação dessa expressão emocional.

É também por estes anos que o Black Mountain College se assume preponderante com as experiências de John Cage, Merce Cunningham e Allan Kaprow, Robert Rauschenberg, entre outros. Da pintura à assemblage e aos ambientes (environments), foi um caminho influenciado pelos futuristas italianos, pelo dadaísmo, pela tradução dos textos de Artaud para inglês, pelo budismo Zen[6], e conduziu a matéria artística aos sons, à vista, ao movimento, aos odores, ao toque. Todos os materiais poderiam agora ser objecto de uma nova arte. Nem tão pouco eram necessários actores ou bailarinos para a executar, mais uma vez, democratizando. A galeria Reuben, entrando num movimento anti-expressionista abstracto, transforma-se o centro downtownhappening. É também com George Maciunas, que em 1962 publica os seus primeiros manifestos da Fluxus (umas edições de tipo fanzine), que se começa, de uma outra vertente, a promover a arte viva, a anti-arte, uma revolução da substância que é a arte. Juntamente com George Brecht, Dick Higgins, La Monte Young, etc., movem-se no território do happening e, fazendo uso de uma ideologia de sabor leninista, iniciam um modelo utópico de cooperação entre artistas (em que todos trabalham com e para todos).

O processo assume agora a primazia da produção artística. A multiplicidade de perspectivas e métodos floresce. Já há muito que os Living Theater incentivavam a criação colectiva. Contudo, vai ser na Judson Dance Theater que a dinâmica de grupo, a participação e condescendência entre artistas de várias áreas se tornam a metáfora de um verdadeiro pluralismo. Também aqui começam a coreografar acções quotidianas, fazendo desses movimentos autênticos ready mades. E é sobretudo aqui que a mulher conquista um lugar de liderança e de criação artística em pé de igualdade com todos os outros. De um espaço marginal enquanto arte, a Judson veio a transformar-se na arena central da expressão avant-garde. É aqui que emerge o que mais tarde se vem a chamar dança pós-moderna (nomes como Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Elaine Summers, entre muitos outros, quase todos discípulos ou de Judd, Cunningham, de Anna Halprin, ou da Martha Graham). Uma dança que se pauta justamente por tentar abolir as hierarquias entre os corpos que podem e não podem dançar, e os movimentos e gestos a que se pode (e não se pode) chamar dança. A improvisação torna-se então um dos procedimentos emblemáticos, metáfora da expressão de liberdade, lembrando técnicas surrealistas da livre associação, agora colocadas em dança, como ali ao lado, nos cafés que frequentavam habitualmente (caffe Cino, Wha Café, La Mama) onde igualmente tertuliavam os poetas, e onde o jazz também improvisava. O contacto-improvisação, amplamente incentivado por Steve Paxton tem aqui o seu início[7].

Como já dissemos, era também na Greenwich Village o epicentro dos filmes underground, com Jonas Mekas como o seu grande impulsionador, “organizando a sua força e tácticas”, como disse no Village Voice, uma “força de guerrilha”. Vivendo de instituições alternativas, fazem frente à censura, violando sistematicamente os valores hegemónicos. É também nesta zona da cidade que se junta o teatro Off-Off-Broadway, nomeadamente os Living Theater que fazem o mais radical teatro político, aliando, por via de técnicas ritualistas de inspiração artaudiana, a arte a movimentos pacíficos de libertação. Quando o estilo dominante no teatro era o realismo (de Stanislavski, ou do Actor’s Studio, do seu aluno Lee Strasberg), o teatro avant-gardeOpen Theater de Joseph Chaikin, ou o Judson Poets Theater). Acreditando no carácter comunitário do teatro, estavam convencidos que seria através dele que o mundo poderia mudar, por via de um engajamento político. move-se do psicologismo para a fisicalidade mais concreta, ultra-real (temperada com as ideias abstractas de Artaud, e as políticas de Piscator), e de problemas pessoais para políticos (aqui, teríamos de acrescentar o

Para toda esta fruição artística não havia realmente muito dinheiro, nem grandes financiamentos estatais (apesar do AIR- Artists in Residence). Assim, os projectos eram deliberadamente crus, de baixo orçamento. Paradoxo parece ser o facto de, apesar destas experiências terem com alguma frequência sido alvo de censura, este movimento artístico dotar os EUA (que os artistas ferozmente criticavam) de uma oportunidade para a apologia da liberdade, por oposição a um bloco soviético dito castrador e pouco inovador. Talvez por isso, pouca gente tenha sido presa.

É neste contexto que a performance art se começa a delinear enquanto prática e a performance (mais genericamente) enquanto conceito. Para o que se tornou necessário uma vertente teórica de escrita e problematização de um mundo que agora interessava compreender em termos performativos. Assim, para além de uma crítica muitas vezes sujeita a critérios hegemonistas, surge em 1979, na New York University, interligando a prática teatral e artística da época (com a diluição de fronteiras que, como até agora se viu, a caracteriza) com um olhar antropológico e teórico (da linguística ao pós-estruturalismo), o primeiro departamento devotado exclusivamente à performance, o Department of Performance Studies. Um pouco antes desta realidade institucional, foi a combinação da pesquisa teatral de Richard Schechner (um dos mentores do então Performance Group – de onde mais tarde sairá o Wooster Group) com a antropologia mais simbólica e interpretativa, sobretudo do estudo do ritual, de Victor Turner, que nasce o interesse por esta área de estudos. Rapidamente a ideia institucional se alastra a outras universidades (em Northwestern University of Chicago, nasce em 1984 um departamento com este nome). Integrando diferentes disciplinas como a filosofia, a linguística, os estudos do género, a sociologia, a psicologia, e as teorias da arte, passa-se a estudar todo e qualquer interacção dinâmica que constitui a experiência. A performance art surge, aqui, em contexto, como o território predilecto, capaz de subverter e criticar não somente a mercantilização dos artistas mas das temáticas socioculturais que trabalham.

Performa Biennial of New Visual Art Performance: breve incursão nas razões de ser do festival

Em 2004, a historiadora e crítica de arte RoseLee Goldberg, autora do livro de 1979 Performance Art: from futurism to present[8], criou a Performa, uma associação sem fins lucrativos dedicada à “exploração do papel crítico da performance na história da arte do século XX e a encorajar novas direcções para a performance do séc. XXI.”

Tendo desde o início como principal objectivo a criação de uma entusiasmante comunidade de artistas internacionais para um tipo de práticas performativas de vanguarda, bem como a criação de público para estas práticas, o festival desde o início procurou ancorar-se vivamente na cidade, cuja efervescência[9] dos anos 70, não apenas procura fazer reviver (institucionalmente) como celebra. Performa é, assim, um festival indissociável do que nos habituámos a imaginar como vida artística da cidade de Nova Iorque pós anos 60.

Auto-intitulando-se Biennial of New Visual Art Performance e optando por nunca utilizar o termo “performance art“, RoseLee Goldberg afirma pretender desviar-se de um termo que na sua opinião sempre foi problemático. Diz-então:

“Ninguém se sente muito confortável com este termo que, em geral, é utilizado para descrever uma grande amplitude de trabalhos, cobrindo cerca de 100 anos de história, quando no fundo é um termo dos anos 70. Eu queria evitar este termo e mostrar que os artistas plásticos [visual artists] sempre fizeram performances. Eu não chamaria Laurie Andersen ou Marina Abramovic de performance artists e duvido que elas utilizem este termo para se auto-descreverem. São artistas que trabalham em muitos media, performance inclusive. E além do mais, ao procurar levar este tipo de materiais a um público mais abrangente, coisa que é da natureza de uma bienal, era importante deixar bem claro que se trata de cobrir um espectro alargado de media e de arte”.

RoseLee Goldberg in PERFORMA 09, “Keeping History Alive”, artigo de Cristiane Bouger no Movement Research Performance Jornar nº35

Uma Bienal que se faz desejar

Como o acompanhamento desta edição deixa bem entrever, as duas edições anteriores da Performa — 2005, ano em que a bienal arrancou; e 2007, ano cuja programação, já mais temática, dedicada tanto às interligações entre a dança de vanguarda e o mundo da arte como a um esforço de “re-imaginação do passado” onde o célebre remake da performance de Kaprow se inseriu — ajudaram a consolidar a bienal como acontecimento que se faz desejar antecipadamente e de que se fala depois de ter passado.

É que a Performa condensa em 20 dias a efervescência artística que nos habituámos a associar à cidade de Nova Iorque. E o faz por via de um esforço consciente que procura, em simultâneo, inscrever a história da performance na vida da cidade (história principalmente tal como Goldberg a escreveu, mas não só) e favorecer o seu desenvolvimento futuro enquanto género artístico. E isto funciona, mesmo que de um modo institucional.

Quando confrontada com este paradoxo, Goldberg, para quem a bienal se encontra muito relacionada com a cidade de Nova Iorque e a revitalização do seu “ethos” artístico e experimental e pode ser definida como uma espécie de “activismo cultural que é uma forma de urbanismo do séc. XXI”, responde:

“A performance art tem uma longa história, por isso depende sempre do período de que falamos. [Como] o mercado de arte também tem uma longa história, a relação entre os dois está sempre a mudar. Em 1920, em Paris e em Berlim, o mercado para a arte contemporânea era limitado. Os acontecimentos Dadas atraíam aqueles que estavam envolvidos no mundo da arte e as pessoas pagavam para ver “Relache”, de Picabia , ou “As maminhas de Tirésias”, de Apolinaire. Quarenta anos mais tarde, nos anos 60, quando já existia um mercado de arte mais forte e vibrante (expressionismo Abstracto, Pop Art) a performance era uma actividade contra o mercado e, em simultâneo, uma arma activista numa época política e socialmente conturbada. Nos anos 70, quando os Artistas Conceptuais protestaram activamente contra a arte-mercadoria, a performance atingiu o seu apogeu enquanto expressão artística privilegiada para as estratégias conceptuais. Nos últimos 10 anos, a força do mercado da arte fez com que muitos artistas estabelecidos e que trabalham em performance começassem a pensar que seria justo o seu trabalho ter também um mercado. Ao que se somou o interesse dos museus pelos trabalhos dos anos 70, muitos destes trabalhos baseados em performance. E por último, o facto de o papel do museu se ter alterado radicalmente. [Os museus] actualmente são palácios da cultura que atraem multidões cada vez mais numerosas que estão fascinados pela proximidade dos artistas e pela Live-art. A performance não é um produto, uma mercadoria, mas no entanto a sua produção pode envolver muito dinheiro. É uma questão relevante [a da institucionalização destas práticas e sua decorrente transformação em mercadoria] mas a resposta tem de ser contextualizada historicamente.”

RoseLee Goldberg in PERFORMA 09, “Keeping History Alive”, artigo de Cristiane Bouger no Movement Research Performance Jornar nº35

Performa 2009

Tendo sido apresentado publicamente em Fevereiro de 2009 (com um Banquete Futurista cuja ementa consistiu em pratos cozinhados a partir do livro de Cozinha Futurista de Marinetti) o programa desta edição tem como tema central uma homenagem aos 100 anos do manifesto futurista.

Com uma estrutura organizativa determinada nas escolhas quer dos programadores de mais de 25 espaços da cidade, quer de curadores independentes internacionais (Goldberd utiliza a expressão “longas conversas” para explicar uma programação em que cada escolha, mesmo que não seja uma estreia, é acompanhada desde muito cedo), a PERFORMA 09 reuniu trabalhos de mais de 80 artistas e cerca de 60 instituições, espalhadas pelas 5 zonas da cidade.

Assim, entre exposições, estreias, a celebração dos 100 anos do manifesto futurista (com exposições e performances famosas, entre elas um concerto do instrumento futurista Intonarumori, de Luigi Russolo) a actividade da bienal reuniu nomes já consagrados como Meg Stuart/Damaged Goods com Auf den Tisch! (At the table!), Deborah Hay com If I Sing to You , Yvonne Rainer com Spiraling Down e Tacita Dean com o filme de 16mm Craneway Event, em homenagem a Merce Cunnigham, ou Arto Lindsay com o desfile multidisciplinar Somewhere I Read, mas também emergentes, como a jovem coreógrafa cipriota, radicada em Nova Iorque Maria Hassabi com Solo Show, entre muitos outros.

[1] E aqui chamamos teatro ao que mais adiante chamamos performance, que isto nos nomes é interessante a provisoriedade, e nas delimitações operacionais (teatro/dança/performance…), o que elas nos mostram das negociações em que as coisas se inscrevem no momento em que aparecem (e da história de que se reivindicam).

[2] No ano passado – dossier Festival de Automne/Paris – um festival caracterizado por praticamente não ter centro – percorreram-se vários equipamentos, alguns dos mais interessantes situados nos “problemáticos” subúrbios de Paris (Teatro de Genevilliers, MAC-Creteuill, MC95 Bobigny…).

[3] E pense, por exemplo, em experiências como a do grupo Gutai no Japão.

[4] A obra de Sally Banes com o mesmo nome Greenwich Village 1963 é uma das principais fontes utilizadas neste texto. É de notar que se trata de uma genealogia Norte-americana e escrita por autores Norte-americanos (de que nomes como o de Sally Banes e Roselee Goldberg serão dos maiores expoentes).

[5] Refiro-me aqui a Terpsicore in Baskets, da crítica de dança Sally Banes.

[6] E aqui é notável uma revisitação levada a cabo nos “anos 60” do que terão sido as experiências dos primeiros modernismos dos anos 20/30. É também considerável (como, aliás, também nestes primeiros era,) a influência que as culturas do chamado mundo não ocidental irão ter.

[7] É aliás, muito interessante ver em alguns vídeos desta época (ou ler as primeiras revistas Contact Quarterly) e entrever o que terão sido as primeiras experiências de Contact Improv. e o tipo de corporalidade “democratizada” (todas as superfícies do corpo como superfície de contacto/ todos os corpos) que esta propunha.

[8] Recentemente editado em Portugal pela editora Orfeu Negro com o título A arte da performance. É de notar que este livro é de 1979 e a sua publicação é inseparável do esforço de nomeação que estas práticas, à época pouco comuns, estão a ser alvo. Roselee procura com esta obra legitimar e enquadra-las na história da arte , para o que as insere na linha das práticas dos primeiros modernismos.

[9] E Sally Banes fala de um”corpo efervescente” como característica da corporalidade desta época (visível em muitas das performances de então: do Paradise Now dos Living Theatre a Meat/Joy de Carolee Schneemann).

Ana Bigotte Vieira é doutoranda em Estudos Artísticos na Universidade Nova de Lisboa/Bolseira da FCT (Visiting Scholar em Performance Studies na NYU – Tisch School of the Arts) e Ricardo Seiça Salgado é performer e doutorando em Antropologia no Instituto Universitáro de Lisboa/Bolseiro FCT/Visiting Scholar em Performance Studies na NYU – Tisch School of the Arts. Membro do Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia (CRIA).

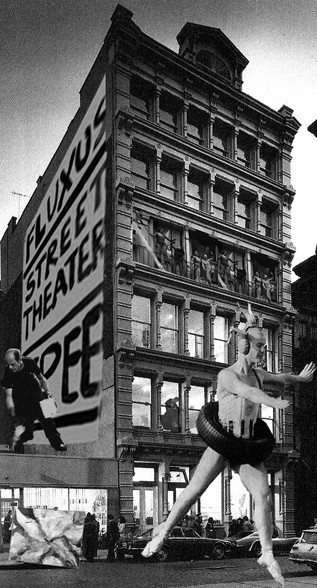

A fotomontagem que ilustra o texto é de Joana Bem-Haja.

Leia também: ‘Auf den Tisch!’, por Meg Stuart e Trajal Harrell

Conversa futurista entre Chameki e Lerner

In case we think that attending a festival in a city also has to do with learning about the city itself (isn´t it what theater is about?), thing get complicated because there are places and there are the stories of the places. But on the other hand, things became a lot less abstract[2]. Therefore, attending a specific festival becomes really different attending any other festival. And it may not even become a marathon.

Our intention is never to geographically “situate” the only and fixed “origin” of a concept and of a set of practices that seem to unfold in similar ways in different countries [3]. We seek to understand some of the connections between thing and places: in this case, the emergence of performance art, at the end of the 50’s and the specific context of the city of New York (with the emergence of Performance Studies in the 70’s and the post-modern dance experiences of the Judson Church Theatre). Enlightened by this brief contextualization, the idea is that we might be able to better understand the genealogy the biannual festival Performa claims as its own (and thus, it helps to establish).

Performance Art. Nova Iorque, anos 1960s.

In the fall of 1959, in New York, Allan Kaprow peformed his famous 18 Happenings in 6 parts in which the term happening was coined (the remake created by André Lepecki was part of Performa 07).

At the time (the early 60’s), Greenwich Village and Soho were the most “alternative” neighborhoods, a kind of “Mecca of the bohemian” (this was largely due to AIR- Artists in Residence, a program for financial support from the government for artists to rent lofts that spread over downtown). There was an ebullient spirit in the avant-guard scene, an atmosphere of confidence, pleasure and transgression. Everything was linked to the political context in the world in general, and specifically in America, with the protests against the Vietnam war and the general feeling of optimism and hope in a radical political change (a point in which it is stated that “the personal is political”).

The explosion of Pop Art takes place in 1963 and 1964. The Judson Dance Theater was at its height with its experiences of democratization of the dancing body (and it is not by chance that one of their main pieces is about dancing with tennis shoes) and of the movements that could be considered dance (experiences such as Trisha Brown’s roofdances or Yvonne Rainer’s use of daily tasks movements). The Judson Poet’s Theater had won 5 Obie awards (the tribute to Off-broaway handed out by the iconic avant-guard newspaper, The Village Voice). Living Theater was at its golden moment. Andy Warhol started to make pop films, Kenneth Anger made his Scorpio Rising and Jack Smith did Flaming Creatures (films that faced censorship in a democratic society and were defiantly screened, for they were banished from the established circuit).

It is also then that Fluxus arrives at New York and Charlotte Moorman organizes the first avant-guard festival. As Sally Barns tells us, growing expectations begin to feed social and cultural changes. At this point, the Greenwich Village becomes a paradigm of such transformations through art.

The avant-guard artists of the 60’s (who can be summoned into about a hundred and fifty people) sought to build a community through art, an alternative community inspired by folk and popular culture that produced transgressive styles, starting cooperative modes of production, going against the alienation of labor and the values reproduced by the preceding generation of artists, as well as the social-political mainstream. In fact, it was not about reflecting the society they lived in, but changing it, producing a new culture that integrates artistic work and life and blurs the borders between participant and observer.

The happening appears as an expression of freedom, spontaneity, a radical way of combining life and art, disfiguring the hegemony of galleries and museums in the control of artistic production and expression. With Jackson Pollock, the brush strokes had already been freed from the canvas, transforming painting in a performing event by spreading the paint on the canvas (which then becomes an index of action), the consummation of that emotional expression.

It was also in those years that the Black Mountain college becomes preponderant with the experiences of John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Allan Kaprow, Robert Robert Rauschenberg, among others. From painting to assemblage and the environment, the path was influenced by the futurist Italian artists, by Dadaism, by the translation of Artaud’s writings to English, by Zen Buddhism [6]. It conducted artistic matter to sounds, sights, movement, smells, touch. All materials could now be the object of a new art form. Actor and dancer were no longer needed to perform it, once again democratizing. Starting an anti-expressionist movement, the Reuben gallery becomes the downtown center of happening. Also, with George Maciunas publishing the first Fluxus manifests (in fanzine-like editions), a new trend begins, the promotion of live art, an anti-art, a revolution of the substance of art. Along with George Brecht, Dick Higgins, La Monte Young, they move in happening territory and using a Leninist flavored ideology, they started an utopian form of cooperation between artists (in which everyone works with and for everybody).

The process now becomes the center of artistic production. The multiplicity of perspectives and methods flourish. Living Theater had been encouraging collective creation for a while. However, it was at the Judson Dance Theater that group dynamics, the participation and complicity between artists from different areas, becomes the metaphor of true pluralism. This was also when daily actions started to be choreographed, making such movements actual readymades. And this is where women conquer a role of leadership and artistic creation in an equal basis. From a marginal position in the art scene, Judson went on to become the central stage for avant-guard expression. This was where what would later be called post-modern dance emerges (names like Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Elaine Summers, among many others, most of whom were disciples either of Judd, Cunningham, Anna Halprin, or Martha Graham). A dance based exactly on the abolishment of hierarquies between the bodies that can dance and those that can not and the movements that can be called dance and those that can not. Improvisation then becomes one of the emblematic procedures, a metaphor for freedom of expression, recollecting surrealist techniques of free association, now applied to dance. In the cafés (caffe Cino, Wha Café, La Mama) they usually sat side by with poets and musicians improvised jazz. Contact-improvisation started here, strongly encouraged by Steve Paxton. [7]

As we’ve said before, the Greenwich Village was also the epicenter of underground films, with Jonas Mekas and his great propeller, “organizing its strength and tactics, a guerilla force”, as he told the Village Voice. Living out of alternative insitutions, they opposed censorship, systematically violating hegemonic values. This is also the area where Off-Off-Broadway theater gathers, namely the Living Theaters that created the most radical political theater, combining through ritualistic Artaudian techniques art with peaceful liberation movements. At a time when realism was the dominant style in theater (Stanislavski, or the Actor’s Studio of his pupil Lee Strasberg), avant-guard theater moves from psychologism to a more concrete physicality, ultra-real (seasoned by Artaud`s abstract ideas and Piscator’s policies) and from personal issues to political ones (here we must add Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theater or Judson Poets Theater). Trusting in theater’s communitarian quality, they were convinced the world could change through it, through political engagement.

There wasn’t really much money for all this artistic fruition, nor there were great government fundings (despite of AIR- Artists in Residence). Thefore, the projects were deliberately raw, low budget. The paradox seems to be the fact that even though these experiences were often censored, this artistic movement gave the USA (which the artists fiercely criticized) an opportunity to support freedom, in opposition to the castrating and non-innovating Soviet bloc. Maybe that’s why few people were arrested.

It was in such context that performance art started to be outlined as artistic practice and performance (more generically) as concept. That is why a theoretical approach in writing became necessary, as well as a problematization of a world that could be understood in performative terms. Thus, the first department devoted exclusively to performance studies was created by the New York University, in 1979. Beyond a kind of critique subjected to hegemonic criteria, the studies interconnected the time’s theatrical and artistic practice (with its blurring of borders) with a anthropological and theoretical perspective (from linguistic to poststructuralism). A little before this institutional reality came about, the interest in this kind of study started with the combination of Richard Schechner’s (one of the mentors of the Performance Group, which later originated the Wooster Group) theatrical reseach with a more symbolic and interpretative anthopology, specially Victor Turner’s ritual studies. The institutional idea soon spread to other Universities (a performance studies department was created at the Northwestern University of Chicago, in 1984). Integrating different disciplines such as philosophy, linguistics, gender studes, sociology, psychology and the art theories, each and every dynamic interaction that is part of experience. In this case, performance art appears in context, as the territory of choice, able to subvert and criticize not only the mercantilization of artists but also the social and cultural issues they tackle.

Performa Biennial of New Visual Art Performance: a brief incursion into the purposes of the festival

In 2004 art historian and critic RoseLee Goldberg, author of the 1979 book Performance Art: from futurism to present, created Performa, a non-profit Association dedicated to the “exploration of the critical role of performance in the history of art of the 20th century and encourge new paths for performance in the 21th century.”

The creation of an exciting community of international artists for avant-guard performing practices had been the festival’s goal from the beginning, as well as the development of an audience for those practices. The festival has always sought to be deeply anchored in the city, not only aiming to re-live (institutionally) but also to celebrate its ebullience in the 70’s. Thus, Performa is inseperable from what we used to imagine as New York’s artistic life after the 60’s.

Self-entitled Biennial of New Visual Art Performance and choosing to never use the term “performance art”, RoseLee Goldberg states that she intends to avoid a term that has always been problematic in her opinion. She says:

“Nobody is comfortable with it. It is used very generally to describe a broad range of work covering a hundred year history, when in reality the term is more speci?c to the ‘70s. I wanted to avoid the term, and to show that visual artists have always made performances. I do not call Marina Abramovic or Laurie Anderson performance artists and I doubt it is a term that they use to describe themselves. They are artists who work in many media including performance. In addition, in bringing this material to a wider audience, which is the nature of a biennial, it was important to indicate that we covered a broad range of art and media.”

RoseLee Goldberg in PERFORMA 09, “Keeping History Alive”, article by Cristiane Bouger at Movement Research Performance Jornar nº35

A Biennial to be desired

As we could see by attending this edition of the festival, the past two editions of Performa helped consolidate the festival as an event that is strongly antecipated and much talked about afterwards. In 2005, the biennial took off and in 2007, the already more thematic program focused both on the interconnections between avant-guard dance and the art world and on an effort to “re-imagine the past”, in which the famous remake of Kaprow’s performance was inserted.

Performa condenses in 20 days the artistic ebullience we are used to associate to the city of New York. And it does so through a concious effort to simultaneously insert the history of performance in the city’s life and to foster the future development of performance as an artistic genre. And it works, even if in an institutional way.

For Goldberg, the biennal is very much related to the city of New York and to the revitalization of its artistic and experimental “ethos” and can be defined as a kind of “cultural activism that is a form of urbanism of the 21th century. When confronted with this paradox, she says:

“Performance art has a long history, so it depends which period we are talking about. So does the art market have a long history and the relationship between the two is always changing. In 1920s Paris and Berlin the market for contemporary art was limited. Dada events attracted art crowds and people paid to see Picabia’s “Relâche” or Apollinaire’s “Mamelle de Teresias.” Forty years later, in the 1960s, when there was a more vibrant art market (Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art) performance was an anti-market activity that was also a weapon of activism in a social and politically volatile period. In the 1970s, when Conceptual Artists actively protested the art commodity, performance was at its height, the most visible art form in relation to conceptual strategies. In the last ten years, the very strong art market made many established artists working in performance begin to think that it was only fair that their work might have a market too. In addition, museums had to incorporate the ‘70s in their collections, and were forced to recognize that much of the work from that period was performance-based. And ?nally, the role of the museum has changed radically. They are culture palaces that attract large crowds who are fascinated by proximity to the artist and by live art. Performance is not an art product in the commodity sense of the word, but it can nevertheless cost quite a lot to produce. The question is relevant but the answer is a larger historical one.”

Performa 2009

The program of last year’s edition of the festival was publicly announced in February 2009 (in a Futurist banquet with dishes prepared according to Marinetti’s Futurist Cook Book). The central theme was a tribute to the 100th anniversary of the futurist manifest.

With an organizational structure based either on the choices of programmers of more than 25 venues or those of international independent curators (Goldberg uses the expression “long conversations” to explain a program in which every choice is followed closely, even when it’s not about a premiere), Performa 09 gathered works from more than 80 artists and about 60 institutions, spread over the city’s 5 boroughs.

Thus, amidst exhibitions, presmieres, the 100 years celebration of the futurist manifest (with famous exhibitions and performances, including a concert with Luigi Russolo’s futurist instrument, the Intonarumori) the biennial gathered acclaimed names such as Meg Stuart/Damaged Goods with Auf den Tisch! (At the table!), Deborah Hay with If I Sing to You, Yvonne Rainer with Spiraling Down and Tacita Dean with the 16mm film Craneway Event, a tribute to Merce Cunnigham, or Arto Lindsay with the multidisciplinary parade Somewhere I Read. New-coming artists were also present, like Maria Hassabi, a young Cypriot choreographer, based in New York, who presented Solo Show.

The photomontage at the top was created by Joana Bem-Haja.

Ana Bigotte Vieira is a doctor candidate in Artistic Studies at Universidade Nova de Lisboa and has a FCT scholarship (Visiting Scholar em Performance Studies at NYU – Tisch School of the Arts) and Ricardo Seiça Slagado is a performer and doctor candidate in Anthropology at Instituto Universitáro de Lisboa (Visiting Scholar em Performance Studies at NYU – Tisch School of the Arts). He is also a member of Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia (CRIA).

Read also: ‘Auf den Tisch!’, by Meg Stuart and Trajall Harrel