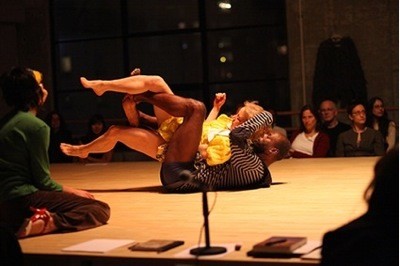

‘Auf den Tisch!’ por Meg Stuart e Trajal Harrell | ‘Auf den Tisch!’, by Meg Stuart and Trajall Harrel

Cristiane Bouger entrevistou Meg Stuart e Trajal Harrel sobre o projeto Auf den Tisch!, apresentado no dia 6 de novembro de 2009 durante a Performa 09, que aconteceu no Howard Gilman Performance Space/Baryshnikov Arts Center, em Nova York. Este texto foi publicado originalmente no Critical Correspondence.

::

Cristiane Bouger: Eu gostaria de começar pedindo que você fale sobre a partitura de improvisação e mais especificamente sobre como você estabelece a sequência da improvisação. Como você trabalha esta estrutura?

Meg Stuart: Para este projeto ou em geral?

Cristiane: Para este trabalho especificamente.

Meg: A primeira coisa é a configuração, que é uma proposta bem clara e que tem estado em todas as edições de Auf den Tisch! Então, a configuração é muito específica por causa do contexto, não é uma improvisação geral, mas o espaço indica que há uma conferência. Há uma indicação de que estamos em uma situação de conferência e estes quatro microfones na nossa frente são sempre a imagem inicial, o ponto de partida, o que indica aos performers que o diálogo, a troca e o debate são tão importantes quanto o movimento. Eu comecei pedindo que cada performer trouxesse algo, uma partitura, uma proposta ou uma posição que eles gostariam de colocar na mesa, e tivemos alguns ensaios. Nos encontramos na terça (3 de novembro de 2009) para o primeiro espetáculo, que foi na sexta (6 de novembro de 2009) e encontramos a plateia para o ensaio geral, quando ficou claro quais eram as questões dos performers. Eu diria que é um tipo de partitura solta que funde as pessoas numa coisa só.

Cristiane: Então você não estabelece uma sequência a partir das partituras que cada performer trouxe durante os ensaios?

Meg: Não. De maneira alguma.

Cristiane: As coisas simplesmente acontecem?

Meg: Eu acho que elas acontecessem pelo diálogo, porque existem intenções que os outros performers colocam. Nós queremos conversas íntimas, queremos falar sobre certos assuntos e as coisas são colocadas neste período de ensaio e estão à mão para serem acessadas pelas pessoas durante a performance.

Cristiane: Isto é interessante. Então, cada performer tem que entender o momento para trazer sua questão específica para a mesa… Não há sequência, de forma alguma?

Trajal Harrell: Não.

Cristiane: O que me fez pensar que havia? Eu realmente achei que havia.

Meg: É o começo. E eu esqueço de me prender a esse começo porque acho que isso significa ouvir, e todo mundo está falando sobre o corpo, e na verdade estão falando sobre um corpo compartilhado e um corpo de conhecimento compartilhado… Meio que sintoniza a plateia para aquele tipo de espaço democrático, porque estamos todos naquele espaço de escuta e nós já estamos expressando isso. O input sonoro é tão importante quanto o visual. E isto está colocado bem no começo. Eu acho que é um começo bem claro.

Cristiane:Sim. É o tipo de projeto que depende muito da habilidade de ouvir e perceber o momento certo para trazer as coisas à tona, mudar ou alterar o que está acontecendo. Como é para você perceber isto como performer e como lidar com este tipo de informação?

Trajal: É muito específico da estrutura de conferência. Eu acho que é uma proposta tão forte exatamente por ser em uma conferência. Acho que realmente tentamos não brincar de conferência. Estamos em uma discussão, estamos desenvolvendo um certo jeito de pensar sobre a improvisação, um certo jeito de improvisar e estamos em conferência, então ouvir é inevitável e intrínseco a uma conferência. Quanto aos performers, isto tem que ser negociado através da escuta e da fala e da performance, todas estas coisas requerem um nível de história que desenvolvemos nos ensaios, como Meg estava falando. Eu acho que quando se trata de ouvir, não é radical. Porque precisa ser, você precisa ouvir para realmente funcionar.

Meg: Eu acho que se você traz um grupo internacional de performers e improvisadores e os coloca eles juntos e diz: ‘Ok, agora vocês vão performar, esse tipo de compartilhamento de conhecimento e essas negociações, esse encontro, diversas línguas, estar no momento, ouvindo e respondendo, tudo isso já está presente. De alguma forma, só estamos fazendo com que isso seja mais visível. Torna-se visível pela maneira como o espaço é delineado, mas já está presente quando bons improvisadores estão juntos. Mas de alguma forma, estamos sintonizando ou amplificando isso, então fica mais presente para o público. Acho que tem uma camada para o público, mas existe outra camada para os performers, na qual eles têm também a chance de apontar, de refletir, não apenas de dançar, mas também de ter um discurso compartilhado sobre improvisação. Outro assunto.

Cristiane: Ok… mas eu quero apenas mencionar que achei isso muito interessante porque mesmo que seja implícito à improvisação escutar o corpo do outro, e nesse caso o discurso do outro também, tendemos a considerar que falar é mais importante do que ouvir. Eu senti que houve uma negociação interessante que você nos permitiu experimentar junto com os performers no exato momento em que eles estão lidando com estas questões. Falando de performers, como você chegou a este grupo específico de artistas? Refiro-me ao elenco de Nova York.

Meg: Eu queria algumas pessoas de Nova York e algumas pessoas da Europa, e não necessariamente um grupo confortável, mas um grupo que estivesse conectado de alguma forma ou ao qual eu me sentisse conectada. Yvonne Meier, por exemplo, eu conheci há 20 anos e até estudei com ela um pouco e estava muito interessada em sua abordagem de partituras. Keith Hennessy eu acabei de conhecer, ele fez minha oficina em um encontro bem curto e intenso. Eu queria também um grupo maduro e um grupo no qual houvesse uma certa tensão por haver diferentes ideologias, diferentes práticas, diferentes tipos de abordagem. Eu também queria bailarinos/performers que eu conhecesse bem – Vânia (Rovisco) já esteve em meu trabalho e trabalhamos juntas por cinco anos. Mas ela é de outra geração, está improvisando por si só. E daí Anja (Müller) está no meu trabalho atual, então é alguém com quem passei um ano improvisando diariamente no estúdio. Pessoalmente, estou interessada em diferentes abordagens, diferentes histórias para cruzar. Eu queria pessoas que fossem pensadores, que se sentissem confortáveis para falar e que pudessem passar fluentemente da ação para a reflexão, da fala ao ato.

Trajal: Exatamente. Eu acho que foi também a minha contribuição, já que conheço um pouco a cena de Nova York. Eu estava tentando achar pessoas diferentes que tivessem uma relação com a improvisação, mas que viessem de pontos de vista diferentes, ou de ideologias ou metodologias diferentes. Acho que isso foi fundamental porque, é claro, David, Yvonne e eu somos muito diferentes. Yvonne tem um forte legado de improvisação em Nova York e ela é de certa forma um símbolo da história da improvisação em Nova York. E David Thomson é alguém muito conhecido por ser esse bailarino incrível em Nova York, mas ele também tem improvisado muito. Ele vem com a história de Trisha Brown em seu corpo, e ele tem trabalhado com Ralph Lemon, entre outros. Acho que a improvisação tem sido boa parte de sua prática ao trabalhar com estes coreógrafos. Conheço George Emilio Sanchez como alguém sobre o qual ouvi falar muito e que tem muita opinião. Ele também tem uma relação muito direta com esta história e esta cena, pois ele tem atuado como membro do conselho do Movement Research e ele atua muito em espetáculos do mundo da dança. Então pensei que ele seria alguém que traria uma acuidade muito verbal para tudo isso, mas também poderia se relacionar, pois ele tem uma relação com a prática de palco. No meu caso, estudei improvisação mais enquanto um jovem estudante de teatro, muito mais do que hoje. Quer dizer, só agora está começando a fazer parte da minha pesquisa e da maneira como componho. Por querer certas possibilidades no trabalho, improvisação é uma forma de trazer outro tipo de textura para o trabalho. Acho que muitos coreógrafos estão usando a improvisação desta forma hoje em dia… Mas preciso dizer que o meu sentido de improvisação mais forte vem de ser uma criança muito pequena na igreja Afro-americana e presenciar o sentido de linguagem verbal e física extraordinária que acontece lá. Isso é o que eu me lembro mais. Quando ouvi falar de improvisação, pensei ‘Ah, isso tem muito a ver com o que estava acontecendo no meu tipo de cultura sulista’. Mesmo meu avô cantando na varanda. Meu avô cantava blues o tempo todo na varanda. Ele tinha um grupo e eles cantavam quando se reuniam em sua casa. Era muito normal. E, às vezes, garotos na rua começavam a ensinar uma nova dança e era sempre improvisado. Mas na minha prática artística, eu nunca fui muito fundo na improvisação ou no contato-improvisação. Apesar de eu ter eu sempre ter observado, não fazia parte da minha prática de estúdio.

Cristiane: Eu acho que existe uma divisão e um tipo de conflito entre trabalhos que são ensaiados e trabalhos que são improvisados, mas você estava dizendo que muitas danças são improvisadas; improvisar é uma coisa natural. Nas danças de rua, as pessoas lidam com isso de forma mais natural. E trazer isso para o espaço da performance – embora haja toda uma história de improvisação –, é interessante por colocar a questão em uma conferência onde as pessoas podem olhar de um ângulo diferente e discutir ou assistir a uma discussão sobre improvisação de uma maneira, talvez, mais formal. Já que uma conferência é algo muito formal em relação a uma prática que é, de alguma maneira, oposta a este tipo de estrutura estabelecida.

Trajal: É, é muito difícil. É isso que faz com que Keith seja realmente interessante porque ele está também escrevendo sua tese de doutorado em improvisação, não sei bem sobre o que é a sua tese, mas eu sei que ele tem feito muito pela improvisação de diferentes maneiras – e isso também é muito claro quando ele trava um diálogo sobre improvisação na mesa. É muito claro que ele está desenvolvendo uma maneira inteligente de pensar e escrever sobre essas questões. Mas em geral, acho que a linguagem sobre como falamos sobre improvisação ainda está sendo desenvolvida e discutida, e que ainda é uma área discursiva problemática. Até mesmo dizer que a improvisação é ensaiada é questionável para algumas pessoas. Não é algo que não é ensaiado só porque não é repetido. Estamos ensaiando, vamos ensaiar agora.

Meg: Eu sou treinada em Contato [Improvisação] e senti que veio muito facilmente e eu gostei porque me senti muito confortável de alguma forma. Mas então percebi que havia uma grande lacuna no que eu queria mostrar no meu próprio trabalho, o qual se refere aos os problemas de comunicação, coisas que evitam que pessoas fiquem juntas e eu não queria esta… Para mim, as coisas não são necessariamente iguais, não é ‘eu rolo em cima de você e você rola em cima de mim’ e nós tínhamos esse acordo. Normalmente, há muito mais tensão, e eu queria também inserir essa tensão. Então eu estava sempre tentando entender como eu podia usar o Contato, usando alguns de seus princípios ou até mesmo entrando em outros campos – como Contato com artes visuais, Contato com músicos ou espaço – ou de que maneira podemos trabalhar com diferentes linguagens e, não divergências, mas as coisas se tornarem mais dissonantes, umas pressionando contra as outras. Isto tem sido uma busca contínua para mim nas mais diferentes formas.

Cristiane: Uma das coisas que me interessam é a tensão entre a espontaneidade da fala e do movimento e a relação de um certo tipo de pressão em dizer a coisa certa ou coerente para começar um movimento, ação ou reflexão ou rompê-los. Como isso funciona quando vocês estão se apresentando? Como vocês lidam com esta tensão entre espontaneidade e pressão?

(Silêncio)

Meg: Não sei bem o que você quer dizer em termos de pressão…

Cristiane: Basicamente… (olhando para Trajal). Você sabe o que quero dizer, certo?

Trajal: Sim, eu sinto muito isso em performance. Acho que tem a ver com risco e experiência. Quero dizer, os melhores improvisadores estão muito sintonizados de alguma forma. [Para Meg] E você também é muito boa nisso porque eu aprendi muito observando você fazendo isso. É um nível de estar em sintonia com você mesmo, o que está acontecendo com você, e também conhecer o todo tão bem… Você tem um impulso: é hora para este impulso? Claro, se você pensa muito sobre o impulso acaba o matando… Então é uma sintonização e uma constante calibração das coisas… É tocar um instrumento, você está tocando tanto o instrumento da sua performance pessoal quanto o instrumento da performance toda. E isso é o que os melhores improvisadores fazem, eles são capazes de assumir esses riscos, não se preocupar, confiar, entrar fundo, sabe… Eles também são capazes de brincar com aquilo. É um desafio, é difícil, é um inferno. Quer dizer, é isso o que é. Claro, se você tem uma pressão enorme para fazer alguma coisa, para fazer a coisa funcionar, e você não pode simplesmente estar ‘fazendo’ algo o tempo todo.

Meg: É… Acho que contenção e ‘não fazer’ são grandes ações. Isso é uma escolha muito poderosa, muito importante. E também sempre lembrar do contexto. Quer dizer, onde você está para que você não se deixe levar pelo momento e também saber que está em uma linha temporal. É um evento que está marcado no tempo, então há uma diferença entre o primeiro minuto e o décimo minuto e o trigésimo minuto. E também tentar acompanhar, de modo que não esteja simplesmente passando por um carretel, mas algo do tipo ‘Ok, esse evento aconteceu, este evento está acontecendo, esta pessoa está aqui’… Então você realmente sintonizou com o timing da coisa toda também.

Cristiane: Já aconteceu de membros da plateia subirem espontaneamente para falar nos microfones ou para performar com vocês na mesa?

Meg: Não espontaneamente, quer dizer, mesmo no ensaio geral, convidamos dois membros da plateia para dançar no final e no final fizemos algumas perguntas. Eu achei bem interessante. Falamos sobre se ‘há um discurso em Nova York sobre improvisação ou não?’. E daí um dos membros da plateia disse que não há discurso em Nova York. Ponto. E daí alguns membros da plateia deram sua opinião. Então achei bem empolgante quando eles se envolveram na discussão, mas na maior parte não tivemos nenhum tipo de ação sabotadora ou alguém forçando uma barra e acho que eles têm sido muito respeitosos. Quer dizer, parece que estão abertos, mas não se enfiam sem algum tipo de gesto ou convite.

Cristiane: Como você atua como moderadora desta conferência com o tempo da ação? Na noite passada você não interferiu muito, certo?

Meg: Eu não sou moderadora nesse sentido. Quer dizer, eu tenho a configuração e nós [eu e Trajal] escolhemos o elenco juntos, mas eu tenho que ter uma profunda confiança neles e também na natureza da improvisação. Os acordos são feitos pelo grupo – este grupo específico – e eles foram discutidos: como por exemplo, quanto de estrutura temos ou não. E também há um certo nível de confiança, então de alguma forma, no momento do show, eu também estou em uma base igualitária [com os demais performers]. Porque eu acho se você começa a censurar no meio, pode ser muito perigoso. Quer dizer, tem um jeito de dizer ‘Ok, tá faltando isso ou isso é para ser tirado, ou num certo nível, eu quero ver isso’, mas não cortar as pessoas ou podar seus impulsos porque isso pode causar um bloqueio real na expressão do grupo.

Cristiane: Eu gosto de pensar sobre esse corpo político naquele espaço e ao mesmo tempo para pensar sobre o discurso político ou ativista e como em certos momentos isso aparece no trabalho de dança. Muitas vezes me pergunto por que dançar ou porque assistir à dança, ou porque escrever sobre dança e, de alguma forma, para mim, pessoalmente, a coisa mais importante na dança é o ato político de mover o corpo de forma mais livre. Como você se relaciona com isso quando você traz esse tipo de discurso político para a mesa e, é claro, isso vem de pessoas diferentes e suas questões específicas, mas como você percebe esse discurso político e porque isso é tão importante agora?

Trajal: Eu acho que há três maneiras para responder esta questão… Uma é que o pessoal é político, as escolhas que fazemos, as coisas que trazemos para o palco, a maneira como criamos as condições, as práticas que desenvolvemos ao redor do trabalho…

Cristiane: A escolha de estar ali.

Trajal: Isso é político. Para mim, fazer este projeto é político. Eu entro por inteiro porque acredito que é radical e que é importante que a dança tenha uma voz, especialmente em Nova York, e é como alguém disse naquela noite, não há discurso em Nova York. Bem, é verdade, não há discurso e isso é bem marginalizado, sabemos isso sobre a dança de Nova York e muitos de nós estamos constantemente tentando resolver esta questão. Número dois, eu acho que neste contexto da [bienal] Performa, é muito importante falar sobre esta forma. Não é um protesto, de forma alguma, mas é um grande testamento político ter isto no festival, para as pessoas começarem a pensar sobre isto e ver seu valor e ler esta entrevista… porque isso que é incrível nesta forma: há um limite, vamos cair na real, sabe. Balanchine disse que não há irmãos adotivos na dança. E eu sempre me lembro disso por que é realmente verdade. A menos que você diga que ele é o irmão adotivo, é realmente difícil fazer um movimento para entender que aquela pessoa é um irmão adotivo, ok? E acho que irmão adotivo é muito importante porque, é claro, “adotivo” não diz respeito apenas ao irmão, é sobre a política de casamento e divórcio e blá, blá, blá. Então, quando pensamos sobre este tipo de forma, isso permite um outro nível de abordagem da dança, de politizar a dança, de pensar sobre essas questões culturais e sociais da improvisação. Como a Meg disse antes, isso as amplifica de forma que se tornam visíveis para o público. Três, acho que esse contexto de Nova York tem tanta função política e não estou falando apenas sobre educação e fazer as pessoas acharem que isso é bom, mas acho que realmente precisamos re-avaliar o papel das artes na cultura e na sociedade. Meg perguntou outro dia se “os soldados no Afeganistão improvisam?” Quer dizer, isso já diz tudo.

Meg: Acho que há também um cruzamento de formas, quero dizer que há improvisação e há performance, mas dá para ver também que é um tipo de extensão deste interesse renovado pelo Movement Research [Performance] Journal e também, os praticantes podem ter propriedade sobre o seu próprio discurso. É também trazer o discurso de volta para o corpo. Então há duas coisas… Mas não é como se houvesse apenas experts falando sobre o que estamos fazendo ou críticos falando sobre o que bailarinos e coreógrafos estão fazendo, mas eles também estão entre eles pensando “ei, também queremos discutir entre nós, queremos ter este tipo de plataforma para nós mesmos.” Acho que é interessante que todos que estão na mesa como praticantes também estão compartilhando riscos. Às vezes, acho é difícil quando alguém faz um trabalho e um crítico ou expert aparece, mas aqui eu adoro… Acho que é político o fato de estarmos todos nos arriscando em todos os sentidos, mesmo os que estão fazendo perguntas, os que estão respondendo, os que estão deitados no chão, o que fica pelado… e somos todos colocados nesse mesmo nível compartilhado, acho que é isto muito crítico também.

Trajal: Sim.

Cristiane: É muito interessante ver esse aspecto político cada vez mais na dança, porque o teatro tem uma longa tradição de teatro político e a dança está ficando cada vez mais política, não só em termos temáticos, mas também na ação. Este trabalho é uma importante plataforma para refletir sobre isso através desse cruzamento de experiências e questões. Também fiquei intrigada com a foto de uma conferência da OTAN usada para promover o trabalho. Eu consigo ver algumas camadas de significados nesta opção, mas eu gostaria que você falasse mais sobre a decisão de escolher aquela imagem…

Meg: É, acho que todo mundo pode ter imediatamente uma imagem dela, ela fala sobre como as pessoas nesta mesa são experts, mas acho que há toda uma gama de traduções e diferentes pontos de vista. Há muito entendimento, mas também muito desentendimento e lobby… Vamos dizer que as pessoas têm questões… É. Acho que eu só coloquei em outro espaço ao invés de mostrar uma imagem de uma mesa de jantar ou outros tipos de mesa com grandes grupos que se pode imaginar. E também dá para ter claramente a ideia de conferência e que há coisas para serem resolvidas.

Cristiane: E a OTAN é uma organização de segurança e vocês estão falando sobre risco…

Meg: É, pode ser também. Acho que crise e emergência são frequentemente um pressuposto quando se fala de improvisação.

Cristiane: Gosto de pensar sobre como a dimensionalidade das coisas pode mudar completamente nossa percepção. Eu me sinto realmente afetada por aquela mesa enorme e pelo modo como sua imagem poderia virar um palco, mas também flui para a imagem de um espaço de celebração ou uma mesa de conferência… Então, você criou um espaço que pode virar muitos espaços. Você tem algo a dizer sobre o fluxo entre o político, o palco e os aspectos celebratórios?

(Silêncio)

Cristiane: (sorrindo) Talvez seja só a minha interpretação pessoal.

Meg: É…

Trajal: Acho que é pura potencialidade. (pausa) Está tudo lá…

Meg: Eu espero que quando exista uma ação – nem quero chamar de fisicalidade ou movimento – na mesa, que exista outra forma de perceber esta ação… Mesmo que não seja definido ou emoldurado por aqueles que estão falando, mesmo que seja apenas silêncio, quer dizer, movimento com música, quero que pareça que é fala, é expressão… você sabe, não se diz ‘Ok, aqui é a parte de dança’. Mas eu também meio que espero que você perceba diferentemente por causa do contexto. Quer dizer, eu muitas vezes vejo o movimento como texto, vejo como autoria, vejo como expressão. Trabalho com a inteligência de cada parte do corpo e como ele pode expressar e o que mais é expresso entre linguagens e além das linguagens… E tenho muita fé no corpo e no movimento também! É, isso é outra parte, um tipo de plataforma para isso. É parte do que queremos também.

Cristiane: As marcações de luz e som também são improvisadas? Quer dizer, é claro que há deixas, mas eles escolhem o que usar em momentos específicos?

Meg: Eles estão improvisando, não quer dizer não estão preparados, o dia todo ontem Jan (Maertens) estava lá, eles acompanharam nosso encontro e nossas sessões e eu trabalhei tanto com Jan quanto com Hahn (Rowe) – com Hahn por muito tempo, mas com Jan em muitas produções – então, eles estavam improvisando com a experiência de encontrar sintonia e consciência… O Jan tem acompanhado este projeto Auf den Tisch!, mas não há direções estabelecidas… Eles discutem, Jan discute seu conceito comigo, mas eles fazem suas próprias escolhas ao longo da apresentação

Cristiane: Tem alguma coisa importante sobre o projeto que você gostaria de dizer que ainda não discutimos?

(Silêncio)

Cristiane: Informações que você gostaria de compartilhar sobre o futuro do projeto?

Meg: Não há planos para o futuro, embora eu sinta que era o projeto certo, na hora certa, no lugar certo, vamos colocar assim. Eu fiquei realmente feliz com a resposta do público ontem. Com os bailarinos, não é bem gostar ou não gostar ou ter uma boa apresentação… Foi assim… Acho que foi bem profundo e fez com que as pessoas realmente pensassem sobre o que estavam fazendo, pensar sobre que tipo de diálogo estavam tendo e acho que foi um grande encontro. Sabe, eu tenho uma visão de que esta mesa poderia ficar em Nova York e outras pessoas poderiam improvisar nela ou trabalhar nela. Acho que há uma necessidade… Estou curiosa sobre como isso vai movimentar as coisas em relação à troca e à improvisação em Nova York. Espero que movimente.

Cristiane: Como irá ecoar…

Meg: É, os ecos. Estou interessada nos ecos.

Cristiane: Obrigada.

Meg: Obrigada.

Trajal: Obrigado.

Cristiane Bouger é diretora de teatro, dramaturga, performer e videoartista. Ela trabalha e mora em Nova York, onde escreve sobre dança e arte contemporânea para The BraSilians, Movement Research Performance Journal e Critical Correspondence. Ela é membro do Coletivo Couve-flor – Minicomunidade artística mundial. www.cristianebouger.com

Leia também: Conversa futurista entre Chamecki e Lerner

Cristiane Bouger interviewed Meg Stuart and Trajall Harrell about the Auf den Tisch! project, presented on November 6th, 2009, at Howard Gilman Performance Space/Baryshnikov Arts Center, during Performa 09. The interview was originally published at Critical Correspondence.

::

Cristiane Bouger: I would like to start by asking you to talk about the improvisational score and more specifically about how you establish the sequence of the improvisation. How do you work on that structure?

Meg Stuart: For this table project or generally?

Cristiane: Specifically for this work.

Meg: The first thing is the set up, which is a very clear proposal and has been in every edition of Auf den Tisch!. So the set up is not a general improvisation, but indicates that it is a conference. There is a guideline that we are in a conference situation and these four microphones before us are always the starting image, the starting point, which indicates to the performers that dialogue, exchange and debate are as important as movement. I started asking each performer to come with something, either a score, a proposal or a stand which they want to put on the table, and we have some rehearsals. We met on Tuesday (Nov 3rd) for the first show, which was on Friday (Nov 6th) and we met audience for the dress (rehearsal) when it became clear what are the issues of the performers. I would say with that there is a kind of loose score that melts people together.

Cristiane: So you do not establish a sequence from the scores every performer brought to you during the rehearsals?

Meg: No. Not at all.

Cristiane: Things just happen?

Meg: I think they happen by dialogue because there are intentions others put out. We want intimate conversation, we want to talk about certain topics, and things are expressed in this rehearsal period, which are at hand to be accessed by people during the performance.

Cristiane: That’s interesting. So, each performer has to understand the moment to bring his/her specific issue to the table… There is not a sequence, at all?

Trajal Harrell: No.

Cristiane: What made me think it really was? I really thought it was.

Meg: It is the beginning. And I forget to really stick to that beginning because I think it signifies a listening and everybody is talking about the body and it is talking about a shared body and a shared body of knowledge… It kind of tunes the audience for all that kind of democratic space, because we are all in that listening space, and we are already expressing that. The audio input is as important as the visual input. And that is kind of put that way right at the beginning. I think that is a very clear start.

Cristiane: Yeah. It is the kind of project that relies a lot on the ability of listening and perceiving the right moment to bring things out, change or shift what is going on. How to perceive that as a performer and how to deal with this kind of information?

Trajal: It is very specific to the framework of the conference. I think this is such a strong proposal because it is being in a conference. I think we really try not to play conference. We are in a discussion, we are developing a certain way of thinking about improvisation, a certain way of improvising and we are conferencing, so listening is inevitable and inextricable to having the conference. And for the performers, it has to be negotiated through listening and through speaking and through performing, and all those things require a level of history that we develop through rehearsals as Meg was just saying. I think when it comes to the listening it is not radical because it has to be, you have to listen if it is going to function really.

Meg: I think if you bring an international group of performers and improvisers and you put them together and say, “Okay, now we are going to perform”, this sharing of knowledge and these negotiations, this meeting, diverse languages, being in the moment, listening and responding, it is all already present. Somehow we are just making it more visible. It is becoming visible because of the way the space is delineated, but it is already present when good improvisers are together. We are tuning or amplifying that, so it is more present. I think there is one layer for the audience but there is another layer for the performers where they have a chance also to point out, to reflect, not only to dance but also to have a shared discourse about improvisation. Another subject.

Cristiane: OK… but I just want to mention I thought that was very interesting because even though it is implicit to improvisation listening to the other’s body and in this case to the other’s speech too, we tend to consider more important to speak than to listen. I felt it was an interesting negotiation you allowed us to experience together with the performers at the moment they are dealing with that. Talking about performers, how did you arrive to this specific group of artists? I am talking about the cast for New York.

Meg: I wanted to have some people from New York and some people from Europe, and not necessarily a comfortable group, but a group that are somehow connected or that I felt connected to. Yvonne Meier, for example, I met twenty years ago and even studied with her a little bit and I was very interested in her approach to scores. Keith Hennessy I just met recently and he took my workshop in a very intense short meeting. I wanted to have also a very mature group and a group where there would be a certain amount of tension because it would be different ideologies, different practices, different kind of approaches meeting each other. I also wanted dancers/performers that I knew very well—Vania (Rovisco) has been in my work, and we’ve worked together for 5 years. But she is another generation, she is improvising on her own. And then Anja (Müller), is now in my current work so she is someone I just spent a year improvising with everyday in the studio. Personally I was interested in different kinds of approaches, different histories for me to cross. I wanted people that were as much thinkers and that feel very comfortable to speak and that can very fluently go between action and reflection, between talking and doing.

Trajal: I think it was also my input knowing the New York scene a bit. I was trying to find different people who had a relationship to improvisation but who come from a different point of view or different ideologies or methodologies. I think that was essential because, of course, David, Yvonne and I are quite different. Yvonne has a strong legacy of improvising in New York and she is a certain symbol of the history of improvisation in New York. And David Thomson is someone who is quite well known as being this incredible dancer in New York, but he also has been seen improvising a lot. He comes from the Trisha Brown history in his body, and he has worked with Ralph Lemon, among others. I think improvisation has been a good part of his practice working with these choreographers. George Emilio Sanchez I know as someone whom I have heard speak a lot and who is very opinionated. He also has a very direct relationship to this history and scene because he has been a chairman of the board of Movement Research and he performs a lot in shows that are in the dance world. So I thought he would be someone who would bring a very verbal acuity to all of this but also would relate, because he has a relationship to the stage practice. Myself, I studied improvisation more as a very young student in theater, much more so than now. I mean, only now is it starting to kind of be a part of my research and the way I compose. Because of wanting certain possibilities in the work, improv is a way of inviting a different kind of texture in the work. I think many choreographers today are using improvisation in that way… but I have to say my strongest sense of improvisation comes from being a very small child in the African-American church and the sense of the extraordinary vocal and physical language that happens there. This is what I remember so much. When I heard about improvisation, I was “Oh, this is very related to what was going on in my kind of Southern culture”. Even my grandfather singing on the porch. My grandfather sang blues all the time on the porch. He had a group and they would sing when they got together around his house. It was very normal. And sometimes kids on the street would start teaching a new dance and it was always improvised. But in my artistic practice, I never really dug deep into improvisation or contact improvisation. Although I looked at it a lot, it was not a part of my studio practice.

Cristiane: I think there is a division and a kind of conflict between work that is rehearsed and work that is improvised, but as you were saying, many dances are improvised; it is a natural thing to improvise. In street dances people relate to that in a more natural way. And bringing that to a performance space – again, there is a whole history in improvisation -, but I think it is an interesting thing to put that in a conference where people can look at it from a different angle and discuss it or watch a discussion on improvisation in a maybe – more formal way, since a conference is something that is very formal in relation to a form that is somehow opposite of this kind of established structure.

Trajal: Yeah, it is very difficult. That is what makes Keith really interesting because he has also been writing his Ph.D., I can’t say exactly what his Ph.D. thesis is on, but I know that he is doing a lot on improvisation in different ways—and that is very clear when he engages in dialogue about improvisation at the table. It’s very clear that he’s been developing an intelligent way of thinking and writing about these issues. But in general I think the language of how we talk about improvisation is still being developed and still being argued, and that it is still in a kind of discursive problem area. Even to say improvisation is rehearsed is questionable for some people. It is not something that is not rehearsed just because it is not repeated. We are rehearsing; we are going to rehearse now.

Meg: I am trained in contact [Improvisation], and I felt it came very easy to me and I enjoyed it because I felt very comfortable somehow. But then I realized that there was a big gap between what I wanted to show in my own work which is about the problems of communication, things that block people from being together, and I did not want this… For me things aren’t equal necessarily, it is not like “I roll on you, you roll on me” and we have this shared agreement. Normally there is much more tension, and I wanted to also pull out this tension. So I was always trying to figure out how I can push contact by taking some of the principles and either moving into other fields—like Contact with visual artists, Contact with musicians or space—or in what way can we work with different languages and, not disagreements, but things becoming more jarring, pressing up against each other. This has being a kind of ongoing search for me in all different ways.

Cristiane: One of the things that I am interested in is the tension between the spontaneity of speech and movement and the relation of a certain kind of pressure in saying the right thing or the coherent thing to start a movement, action or reflection or disrupt it. So how does it work while you are performing? How do you deal with this tension between spontaneity and pressure?

(Silence)

Meg: I do not know quite what you mean in terms of pressure…

Cristiane: Basically… (Looking at Trajal’s face) You know what I mean, right?

(Silêncio)

Trajal: Yeah, I experience this a lot in performance. I think it has to do with risk and experience. I mean, the best improvisers are very attuned in some ways. [To Meg] And you are very good at this because I have learned a lot by watching you do this. It is a level of being in tune with yourself, what’s going on with yourself, and also knowing the whole so well… You have an impulse: is it the time for that impulse? Of course, if you think about that impulse too much it kills it… so it is an attunement and a constant calibration of things… it is playing an instrument, you are both playing the instrument of your individual performance and the instrument of the whole performance. And that is what the best improvisers do, they are able to take those risks, not worry, trust, go in, deep in, you know… They are able to play with that. It is a challenge, it is hard, it is hell. I mean, that is the thing. Of course, you have a huge amount of pressure to do something, to make the thing work and you can’t just be “doing” all the time.

Meg: Yeah… I think restraint and not doing is a big action. That is a very powerful, very important choice. And also just always remember the context. I mean, like where you are so you are not just carried away by the moment and also know that it is on a timeline. It is an event that it is marked in time so there is a difference between the first minute and the tenth minute and the thirtieth minute. There is also somehow trying to keep track, so it’s not just passing through a reel but somehow there is like, “OK, this event has happened, this event is happening, this person is here”… so you just really have tuned in with the timing of the whole thing as well.

Cristiane: Have you ever had audience members who spontaneously came up to the microphones to speak or on the table to perform with you?

Meg: Not spontaneously, I mean even in the dress rehearsal we invited two audience members to dance at the end and at the end we asked some questions. I thought it was quite interesting. We talked about “is there discourse in New York or not about improvisation?” And then one of the audience members says there is no discourse in New York. Point. And then some of the audience members added their thoughts about that. So I thought it was quite exciting when they get involved in the discussion, but for the most part we have not had a kind of sabotage action or somebody who is pushing and I think they have been quite respectful. I mean, it does seem they are open but they don’t sort of like jump right in without a kind of gesture or invitation.

Cristiane: How do you act as a moderator of this conference with the time of the action? Last night you didn’t interfere so much, right?

Meg: I’m not the moderator in that sense. I mean, I had the set up and we together [with Trajal] chose the cast, but I have to have a profound trust in them and also the nature of improvisation. The agreements are made by the group—this specific group—and they are discussed: how much structure we have or not. And there is a certain amount of trust, so somehow, at the point of the show, I am also on pretty much equal ground. Because I think if you start censoring in the midst of that it can be quite dangerous.

I mean, there is a way to say like “OK, this is missing, I will put my input in or this thing is to take off, or on a certain level I want to see this”, but not to sort of cut people off or sort of clip their impulses because that can cause a real blockage to expression in the group.

Cristiane: I like to think about this political body on that space and at the same time to think about the political or activist speech and how in certain moments it appears in the dance work. Many times I keep asking myself why to dance or why to watch dance, or why to write about dance, and somehow for me, personally speaking, the biggest thing about dance is the political act of moving the body in a freer way. How do you relate to that when you bring this kind of political speech to the table, and of course, it comes from different people and their specific issues, but how do you perceive this political speech and why this is so important right now?

Trajal: I think for myself there are three ways I can answer that question… one is that the personal is political, the choices we make, the things we put on the stage, the way we create the conditions, the practices that we develop around work…

Cristiane: The choice of being in it.

Trajal: This is political. For me, doing this project is political. I step into it fully because I believe it is radical and it is important that dance have a voice, especially in New York, and it is like someone said that night, there is no discourse in New York. Well, it is true, there is no discourse and it is quite marginalized, which we know about dance in New York and many of us who are working in dance are constantly trying to solve this. Number two, I think within this context of Performa, it is very important that we talk about this form. It is not at all a protest, but it is a great political testament to have it in this festival, and for people to begin thinking about it and to see its value and to read this interview about it… because that is what is incredible about this form: there is a limit, let’s get real, you know. Balanchine said there are no stepbrothers in dance. And I always remember this because it is really true. Unless you say he is the stepbrother it is really hard to make a movement to figure out that that person is a stepbrother, okay? And I think stepbrother is very important because of course, “step” is not just about being the brother, it is about the politics of marriage and divorce and blah, blah, blah. So, when we think about this kind of form, it allows for another level of approaching dance, of politicizing dance, thinking about these cultural, social issues around improvisation. Like Meg said before in another answer, it amplifies them in a way that makes it visible for an audience. Three, I think in this context of New York has such a political function, and I am not just talking about education and making people think that is good, but I think we really have to re-evaluate the role of the arts in culture and society. Meg asked the question the other day “do soldiers in Afghanistan improvise?” I mean, that says it all right there.

Meg: I think also it is a crossing of forms, I mean there is improvisation and performance, but you could also see it as a kind of extension of this renewed interest in the Movement Research [Performance] Journal and also, somehow the practitioners themselves can own their own discourse. And it’s bringing discourse back to the body. It is not like there are not experts talking about what they are doing, or critics saying what dancers and choreographers are doing, what are doing, but they are also with themselves saying, “hey, we also want to discuss among ourselves, we want to have this kind of platform for ourselves”. I think it is interesting that everyone that is on this table as a practitioner is also sharing the same risk. Sometimes I find it hard when people make work and then a critic shows up or an expert shows up, but [here] I love it …I think it is political that we are all risking in all senses, even the ones asking the questions, the ones answering, the ones lying on the floor, the one getting naked… and we are all put on this shared level, I think that’s very critical as well.

Trajal: Yeah.

Cristiane: It is very interesting to see this political aspect more and more in dance, because theater has a long tradition of political theater, and dance is getting more and more political not only in a thematic way, but in its action. This work is an important platform to reflect that through this crossing of backgrounds and issues. I am also intrigued by the NATO conference picture used to promote your work. I can see a couple layers of significance in that, but I would like you to talk a little bit about the decision of choosing that picture…

Meg: Yeah, I think everyone can immediately have some sort of image of it, it talks about the people on this table are experts, but I think also there is a whole series of translations and different points of view. There is much understanding, but there is also misunderstanding and miscommunication and lobbying. … Let’s say people have issues… yeah. I think I just put it in another space rather than show a picture of a dinner table or other kinds of tables with large groups that you can imagine. And also you get clearly this idea of conferencing and that there are things to be worked out.

Cristiane: And NATO is an organization about security and you are talking about risk…

Meg: It can be also, yeah. I think crisis and emergency are often a given when you talk about improv.

Cristiane: I like to think about how the dimensionality of things can completely change our perception. I really felt affected by that huge table and the way its image could become a stage but also flows to the image of a celebratory space or a conference table… So, you created a space that could become many spaces. Do you have something to say about that flow between the political, the stage and the celebratory aspects of it?

(Silence)

Cristiane: (smiling) Maybe it is just my personal reading.

Meg: Yeah…

Trajal: I think it is pure potentiality. (pause) It is all there…

Meg: I would hope that when there is an action – I do not even want to call it physicality or movement – on the table, that it is also another way of perceiving it… even if it is not defined or it is not framed by those speaking, even if it is just silence, I mean, movement with music, it feels like that is speaking, it is expressing… you know, you don’t say “Okay, here is the dance part”. But I hope also kind of makes you perceive it differently because of the context. I mean, for me I often see movement as text, I see it as authoring, I see it as expressing. I work with the intelligence of every single part of the body and how it can express someone and what else it is expressing between languages or beyond language… and I have a lot of faith in the body and the movement as well! Yeah, that is also another part, a kind of platform for this. It is part of what we want to push as well.

Cristiane: The light and sound cues were also improvised? I mean, it is clear there are cues, but do they choose what to use in specific moments?

Meg: They are improvising, it does not mean they are not preparing, I mean, all day yesterday Jan (Maertens) was here, they were following our meetings and our sessions and both Jan and Hahn (Rowe) I worked with – I mean Hahn for a very long time but Jan for many productions – so, they were improvising with the experience of the kind to find tune and awareness… for Jan, he has been following this Auf den Tisch! projects, but there are no set directions … I mean, they discuss, Jan discusses his concept with me, but they are making their own choices during the course of the evening.

Cristiane: Is there something important you would like to say about the project that we did not mention?

(Silence)

Cristiane: Information about the future of this project you would like to share?

Meg: There are no future plans, though I feel it was the right project in the right time at the right place, let’s put it that way. I felt I was really happy with the response of the audience last night. With the dancers, it is not about liking or not liking or having a good evening… it was like… I think it ran quite deep and made people really think about what they were doing, think about the kind of dialogue they were having and I think it is a big meeting. You know, I have this vision this table could stay in New York and other people could improvise on it or work on it. I feel there is a need for this… I am curious how that is goinng to move things in relation to exchange and improvisation in New York. I hope it does.

Cristiane: How it is going to echo…

Meg: Yeah, the echoes. I’m interested in the echoes.

Cristiane: Thank you.

Meg: Thank you.

Trajal: Thank you.