CHINA unMADE – ??•?? Chaim Gebber, Enesoe Chan, Galerias – construções | CHINA unMADE – ??•?? Chaim Gebber, Enesoe Chan, galleries – constructions

Sheila Ribeiro/dona orpheline está trabalhando em Nanjing, na China, pelos próximos seis meses. De lá, ela vai relatar suas experiências e observações da cultura local como correspondente do idança.

Island 6 Arts Center

Thomas Charveriat, da galeria Island 6 Arts Center, foi quem me apresentou Chaim. Ele explica que os artistas da dança chineses apresentam mais seus trabalhos na Europa do que na China, por motivos financeiros e pela burocracia. Na Europa (Alemanha e França) existem bolsas para artistas chineses. Na China não.

Além disso, para que um artista apresente seu trabalho em um local com o direito de cobrar ingressos, deve ter um documento, uma licença. Para obtê-la, o artista deve submeter-se a dois procedimentos: um financeiro e um moral. Com o financeiro, descobrimos uma “política pública” que estimula o fim do métier do artista da dança. Para cada evento, deve-se pagar uma soma em torno de 5000RMB (R$ 1.400), 18% de imposto e 20% para o sistema de venda de ingressos “my piao”. O procedimento que chamei de “moral” diz respeito a enviar um vídeo do trabalho para a censura, que o avaliará e devolverá ao artista um feed-back com o que deve ser cortado. A censura proíbe as coisas mais banais que uma censura proibiria: nudez, sexo, falar de política e violência. Como diz Chaim: “não existe maior violência que a censura”. Por isso, a dança contemporânea na China vive nas galerias de arte, que, pelo que entendi, têm muito prazer em compartilhar os trabalhos de dança em seus locais. Sem financiamento direto, os artistas, às vezes, recebem cachês de intermediários culturais europeus.

Art Shaker

Meia hora de táxi me leva do centro de Shangai a uma periferia de horizonte largo, Yangpu, para o Art Shaker. No meio de um centro comercial (com lojas de material de construção, DHL e outros escritórios) o Art Shaker aparece e relembra que a noção de centro versus periferia não se aplica mais à metrópole contemporânea.

Muito novo em tudo o que é, o Art Shaker é um complexo de estrutura enorme, arquitetura de ponta, em quatro setores e cinco andares. Dois andares em funcionamento, com várias galerias. Os outros três, em construção, são ao mesmo tempo o alojamento dos trabalhadores que os constroem. No centro, um espaço a céu aberto, tipo praça, interliga – shakera – praticando o shake que mistura os sabores dos andares, das pessoas, das galerias vivas e das em gestação, sendo liminar dos sentidos da visão, da imensidão, do deslumbramento do céu e da construção. Pedreiros e artistas trabalhando no mesmo espaço – operários, obreiros.

Vinte e cinco “palavras de ordem” estampadas em seu flyer de divulgação orgulhosamente apresentam a visão de mundo deste espaço para as artes multidisciplinares e indisciplinadas (selecionei 10 delas): futuro, mundo, brilho, tempero, explosão, criatividade, artista, arte, sentidos, liberdade. E concluem: “Você está em um fantástico lugar onde negócios, tecnologia, arquitetura, moda e arte estão fervendo”. É mole?

Tomaz Zihunt Chow cura Liminal 800, onde o trabalho de Chaim, One (foto), está programado. Chow se interessa pelo que vem a ser, hoje, a relação dentro-fora, nas dinâmicas e espaços que formam zonas liminares. Questiona os espaços de trânsito geográfico (como corredores e janelas) relacionando-os àqueles sociais (pessoas que seguem regras e as que as quebram) – lembrando que no próprio prédio tem um escorregador que liga o 5º andar ao 1º (ou o contrário). Para ele, o liminar traz incerteza e gera tensão de equilíbrio entre a criatividade humana e a inflexibilidade das regras. Assim, apresenta o conceito de liminaridade como um divisor sutil onde não existem diferenças de gêneros ou disciplinas e onde o latente se faz possível em um transitar instável entre um dentro que não existe mais e um fora ainda impreciso e indefinido. Propõe assim, as instalações interativas criadas por bailarinos e artistas visuais.

Dragoneira

Falando em zona liminar, Enesoé Chan se autodefine como um mestiço sino-brasileiro nascido em Moçambique. Ele é estilista e misturou em seu último projeto os temas do dragão e da capoeira, para ele, casando China e Brasil. Seu slogan é “moda investível, arte vestível, moda consciente”. O conceito de moda investível troca de lugar com o da arte que se pode incorporar como vestimenta e traz desejo e prazer na mutação, na construção. A moda consciente de Chan dissolve a visão de que a moda é uma padronização homologante propondo, antes de tudo, consciência estética da pessoa e da roupa.

Já Chaim Gebber existe porque um sírio e uma chinesa fizeram amor; e também porque dois escravos de Minas Gerais fizeram amor e puderam ter um filho não escravo a partir da Lei do Ventre Livre. Por isso, o conceito multi-prospéctico do shaker, do limiar e da construção transbordam da arquitetura da Art Shaker e da curadorida de Chow pertencendo além da “cultura”, também dos detalhes e cruzamentos biográficos dos dois artistas.

Durante One, de um som grave, obscuro e de pulsação contínua surge a voz de Ney Matogrosso (em uma rápida citação); uma canção de Gilberto Gil é tocada e dançada por completo; uma voz em off fala de mameluco, mestiço, mulato, branco, índio brasileiro – em português; o trabalho de Chaim, apesar de ser evento chinês, relembra que um artista traz consigo experiências, formatações, valores, deslocamentos, sua matéria bruta. Chaim escreve em chinês (algo que não entendo). No encontro com o artista pós-apresentação, uma espectadora pergunta “qual é a sua motivação para nos mostrar isso?” Enfim, um jogo constante de um shakerque é incógnita nas relações contemporâneas onde a tradução não existe e não faz sentido.

One

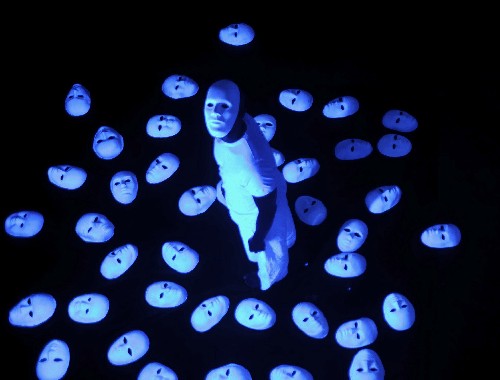

Máscaras brancas espalhadas no chão em um ambiente criado por luzes negras fosforescentes nos levam até os praticáveis. No centro da cena, um homem em pé, de branco, pés descalços – em mix de coisa “oriental”, capoeira e roupa para dançar. Ele está mascarado em meio às mesmas muitas máscaras. Ele está ali, imóvel, mas não intacto, nem passivo. Ele respira e está presente. A presença de Chaim dá vida às máscaras que se tornam cúmplices, vigilantes e em exposição. Com referências nas culturas em que viveu, uma série de ações e relações são objetos-ponte para que Chaim componha um panorama de “contexto”: desde a máscara branca, passando por um bonequinho “beiçudo” (representando um negro?), papéis, escrita e trocas de figurino em cena.

Em termos de background dramatúrgico, o que me pareceu mais “brasileiro” em termos de know-how foi a necessidade de se explicar e de ser “compreendido” em suas peculiaridades; a parte “europeia” seria a estrutura irônica e paródica como se esse tipo de inteligência fosse anti-poder. Segundo a simbologia cromática chinesa, a cor branca tem um sentido de morte e luto. O branco veste-se nestas máscaras comunicando um evento incontrolável ou incompreensível que transforma o rosto vivo (colorido) em máscaras mortuárias replicadas.

A arquitetura de sua dança delimita códigos da ordem do reconhecimento racional e social, onde, por consequência Chaim se mete “a dançar” novamente, ou, quer dizer, a movimentar-se em uma dança de outra ordem, a da abstração. O corpo fica “doce” (chegando à necessidade de dar uma reboladinha tímida – representando um prazer?). Abstrata, porém não tão diferente do mish-mellow que propõe e disseca na “primeira parte contextual”. Sua movimentação vai do deslocar e expressar sensações e sentimentos; a fazer referências e citações; a penetrar em movimentos vindos da capoeira e do releasing em uma bricolagem de formas reconhecíveis e inventadas. Às vezes olha os objetos com uma pseudo estranheza, com a surpresa do primeiro encontro, se colocando também, como objeto de encontro para o espectador. O “si mesmo” se transforma em uma surpresa a cada vez. Ou ainda o “si mesmo” é o “como se fosse” de si mesmo.

Com as máscaras traz as multiplicidades mascaradas que encontra em si mesmo, nos outros, nos grupos constituídos por subjetividades e naqueles de difícil acesso à subjetividade. A máscara singular e plural, forma o “um”. De certa maneira, Chaim parece fazer um convite: o de perceber a singularidade fixa de um rosto – do rosto um – em um escorrer ininterrupto de identidades como os fragmentos de culturas que o artista constroi e shakera.

Enquanto se objetifica, a título de vários exemplos, Chaim tem proposta político-ideológica defendendo a mestiçagem. Transita entre o que domina e o que não, em várias representações de si mesmo propondo múltiplas realidades que, para Chaim, constroi “o um” fragmentado e viajante. O que Chaim tenta fazer do “um” não é criar unificação, nem reproduzir o um como identidade fixa e self, ao contrário, mostra que o um pode existir também dentro de uma porosidade, gordinha, latente, redonda, pulsante, esperançosa. É quando o um não pode ser mais visto por um olhar da tradição intelectual ocidental. Tudo se desloca, se shakera e o um também. Enquanto isso Enesoé Chan e o Art Shaker vestem, revestem, investem e despem.

Sheila Ribeiro/dona orpheline é artista em dança contemporânea, novas mídias, publicidade e cinema. Interessada pelas dinâmicas de poder, trata tensões pós-coloniais, ilusão, deslocamento e desejo na comunicação contemporânea, trabalhando sempre em trânsito. Faz duo com seu marido, o antropólogo Massimo Canevacci Ribeiro. Colabora também com Benoît Lachambre, Laurent Goldring, Sophie Deraspe, Edgard Scandurra, entre outros.

Sheila Ribeiro/dona orpheline is working in Nanjing, China, for the next six months. She will report on her experiences and observations about the local culture as a correspondent for idança.

Island 6 Arts Center

Thomas Charveriat, from the Island 6 Arts Center gallery, was the one who introduced me to Chaim. He explained that Chinese Dance Artists show their work in Europe more than they do in China and so for financial reasons and because of the bureaucracy. In Europe (Germany and France) there are grants for Chinese artists. But not in China.

Besides, once an artist presents her work in a place that has the right to charge for tickets, she must have a document, a license. In order to get it, the artist must submit to two procedures: a financial one and a moral one. Through the the financing issues, we found out a “public policy” that stimulates the end of the Dance artist métier. Each event one must pay a sum of about 5000RMB (R$1.400), 18% taxes and 20% for ticket selling system “my piao”. The procedure I call “moral” involves submitting a video of the work for censorship, which evaluates the material and sends a feedback of what must be cut. The censorship forbids the universal trivial things around censorship itself: nudity, sex, discussing politics and violence. As Chaim says: “there is no greater violence than censorship”. For that reason, Contemporary Dance in China takes place in Art, which – from what I could see – are happy to share Dance works in their spaces Without direct funding, artists often receive their payment through European cultural intermediates.

Art Shaker

A half-hour taxi ride takes me from downtown Shangai to a wide horizon periphery, Yangpu, to Art Shaker. In the middle of a commercial center (with building material stores, DHL and other offices), Art Shaker emerges and reminds us that the idea of center versus periphery no longer applies to the contemporary metropolis.

Very new in everything, Art Shaker is a complex with a huge structure, brand new architecture, with four sectors and five floors. Two floors are already working, with many galleries. The other three, still under construction, are being used at the same time as lodging by the workers building them. In the center, an open sky square-like space interconnects – shakes – practicing the shake that mixes the flavors of the buildings, the people, the alive galleries and those still in the womb, a threshold of senses of vision, vastness, dazzle of the sky and the building. “Opera” workers, side by side.

Twenty five slogans printed in the advertising flyers proudly present the worldview of the space for multidisciplinary and undisciplined arts (I selected ten of them): future, world, shine, seasoning, explosion, creativity, artist, senses, freedom. And the conclusion is: “You are in a fantastic place where business, technology, architecture, fashion and art are sizzling”. Got it?

Tomaz Zihunt Chow curates Liminal 800 where Chaim’s work, One, was shown. Chow is interested in what the inside-out relation means in dynamics and spaces that form liminal zones. He questions the geographic transit spaces (like corridors and windows) relating them to social ones (people who follow rules and people who break them) – keeping in mind that the building itself has a slide that connects the 5th to 1st floor – (or the other way around). For him, the in-between brings uncertainty and creates balance tensions between human creativity and the inflexibility of rules. Thus, he presents the concept of liminality as a subtle divider in which there are no differences between genders or disciplines; where what is latent becomes possible in an unstable transit between an inside that doesn’t exist anymore and an outside that is still imprecise and undefined. Therefore, he proposes interactive installations created by Dancers and Visual Artists.

Dragoneira

Speaking of liminal zones, Enesoé Chan defines himself as a mixed Chinese-Brazilian born in Mozambique. He is a Fashion Designer and in his latest project he mixed dragon and capoeira themes, marring China and Brazil. His slogan is “unwearable fashion, wearable art, conscious fashion”. The concept of unwearable fashion changes place with the one of art. An art that could be incorporated as clothing and which brings desire and pleasure in mutation, in construction. Chan’s conscious fashion dissolves the notion that fashion is homogeneous standardization, proposing, above all, the aesthetic awareness of the person and the clothing.

Chaim Gebber exists because a Syrian man and a Chinese woman made love and also because two slaves from Minas Gerais, a Brazilian state, also made love and were able to have a non-slave son after the “law of the free womb”. That is why the multi-perspective concept of the shaker, of the liminal and of construction overwhelm the Art Shaker architecture and Chow curatorship, belonging – beyond “culture” – also the two artists biographic crossings

During One, from a deep, obscure, continuous pulsating sound emerges the voice of Ney Matogrosso (in a quick citation); a Gilberto Gil song is completely played and danced; a voice-over talks around mameluco, mestizo, mulato, white man, Brazilian native – in Portuguese; Chaim writes in Chinese (something I don’t understand). At the post-show meeting with the artist, a spectator asks “what is your motivation to show us that?” In spite of being a Chinese event, Chaim’s work reminds us that an artist brings along experiences, formats, values, displacements: his raw material. It’s a constant game of a “shaker” that is an enigma in contemporary relationships in which translation doesn’t exist and doesn’t make any sense.

One

White masks scattered on floor in an environment created by phosphorescent blacklights lead us to the scaffolds. In the center of the stage, a man stands, dressed in white, bare feet – a mix of “Eastern” outfit, Capoeira and dance clothing. He is wearing a mask amidst the same many masks. He is standing there, still, but not intact, neither is he passive. He breathes and he is present. Chaim’s presence gives life to the masks that become his witness, survailing and exhibited.

Based on references to the cultures in which he has lived, a series of actions and relations are bridge-objects for Chaim to compose a panorama of “context”: from the white mask to a big-lipped doll (would it be a reference to a “black man”?), papers, writings and costume changes on stage.

In terms of dramaturgic background, what seemed most “Brazilian” to me, in terms of know-how was the need to explain himself and to be “understood” in his peculiarities; the “European” part would be the ironic and parodic structure as if this kind of intelligence were anti-power. According to the Chinese chromatic symbology, the color white has a meaning of death and mourning. The white is dressed in these masks communicating an uncontrollable or incomprehensible event that transforms the living face (colorful) in replicated mortuary masks.

His dance’s architecture outlines rational and social codes through which, therefore, Chaim comes “to dance” again, or, I mean, to move in a dance of a different order, that of abstraction. The body becomes “sweet” (reaching a point where he needed to shyly sway his hips – representing some pleasure?). It is abstract, but not so different from the mish-mellow he proposes and dissects “in the first contextual part”. His movement goes from displacing and expressing sensations and feelings; to making references and citations; penetrating in movements derived from Capoeira and release in a bricolage of recognizable and invented shapes. Sometimes he looks at the objects with pseudo-astonishment, with the surprise of a first encounter, presenting himself also as an object of an encounter with the spectator. “Himself” turns into a surprise at each time. Better yet, “himself” is the “as if” of himself.

With the masks, he brings the masked multiplicities that are found within himself, in others, in groups composed by subjectivities and in those of difficult access to subjectivity. The singular and plural mask creates a “one”. Somehow, Chaim seems to be making an invitation: to realize the fixed singularities of a face – the one face – in an uninterrupted identity slide like the fragments of cultures the artist builds and shakes.

While he objectifies himself, in the quality of several examples, Chaim has a political-ideological proposal and defends miscegenation. He transits between what he dominates and what he doesn’t, in various self representations, proposing multiple realities that, for Chaim, build the fragmented and travelling “one”. What Chaim tries to do with the “one” is not to create unification, neither to reproduce the “one” as a fixed identity and self, on the contrary, he shows that the “one” can also exist within a fat, latent, round, pulsating, hopeful porosity. That’s when the “one” can no longer be seen from a traditional western intellectual perspective. Everything shifts, “shakes” and the “one” also does. Meanwhile Enesoé Chan and Art Shaker dress, redress, invest and undress.

Sheila Ribeiro/dona orpheline is a contemporary dance, new medias, advertisement and cinema artist. Interested in power dynamics, she deals with issues of post-colonial tensions, illusion, displacement and desire, always working in transit. She forms a duo with her husband, anthropologist Massimo Canevacci Ribeiro. She also collaborates with Benoît Lachambre, Laurent Goldring, Sophie Deraspe, Edgard Scandurra, among others.