Corra seu risco | Take your risk

O que me levou à Veneza não foi propriamente o encanto de uma das mais belas (e turísticas) cidades do mundo, ainda que a vontade de conhecê-la existisse há tempos. Também não foi exatamente a companhia dos amigos, que alegraram a minha estadia. Tampouco as férias escolares do verão europeu. Aquilo que realmente motivou minha ida até lá foi a estreia da nova obra do coreógrafo William Forsythe (1949), The Fact of Matter, durante a 53a Bienale di Venezia, que acontece do dia 7 de junho ao dia 22 de novembro de 2009. A bienal é um empreendimento enorme e tudo respira arte pelas ruas, museus, galerias, igrejas, barcos, pessoas. A própria cidade pode ser considerada um museu a céu aberto, pois, fundada no ano de 950, carrega uma longa história que passou pela posição geográfica vantajosa e estratégica entre o Oriente e Ocidente. Nesse sentido, nada mais acertado do que o nome do mercador e explorador Marco Polo para o aeroporto, não?

Antes de comprar meus bilhetes para a exposição (custam 18 euros e dão entrada para as duas áreas por onde o evento se espalha, em Arsenale e Girardini) verifiquei algumas informações no site da companhia do Forsythe, The Forsythe Company. Se você fizer o mesmo que eu, vai perceber que há somente uma “página” com dados que se reduzem ao nome da obra, seu autor, o ano de estreia, a data de exibição, os promotores/realizadores e a palavra “tickets” que, quando clicada, te conduz ao endereço eletrônico da famosa bienal. Com cerca de 90 artistas, não seria difícil encontrar o nome do coreógrafo, caso o sistema de busca do ambiente funcionasse. O resultado dá em nada. O jornal de divulgação do evento apresenta uma lista em ordem alfabética dos participantes, mas o de Forsythe também não consta. Nada nos panfletos e os monitores igualmente não sabiam informar.

Estaria eu diante de uma investigação de detetives?

Como não havia informação coerente disponível, cheguei a pensar que, talvez, a instalação tivesse sido cancelada por algum motivo e algo estivesse virtualmente desatualizado. Diante dessa confusão, do tamanho da exposição e da quantidade de obras, como eu iria, afinal, encontrar a nova obra do William Forsythe, caso ela lá estivesse?

Só indo pessoalmente. Pois foi na terceira visita que, totalmente por acaso, encontrei The Fact of Matter! Logo depois de ter sido felizmente pega de surpresa pelas esculturas da americana Miranda July, enquanto passeava à deriva pelo jardim, em Arsenale. O lugar é um misto de gramado, mata, pedras, pássaros e outros bichos cercado por uma paisagem industrial e portuária com arquitetura do século XVI. The Fact of Matter está praticamente escondida numa parte mais reservada dessa área. Inclusive você só desconfia que tem alguma coisa ali ligada à exposição porque identifica, à distância, o suporte de papel onde ficam os créditos das obras, padrão da bienal.

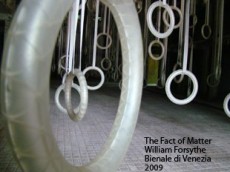

A sala do seu mais recente objeto coreográfico, como Forsythe vem chamando alguns de seus trabalhos, é um lugar aparentemente abandonado e não muito grande. As duas aberturas estão cobertas de vegetação. Há ferrugem e pó. Dentro do lugar, se você não fizer questão de ler os tais créditos com a “explicação” colocada na entrada, será surpreendido por 200 anéis de ginástica pendurados em diferentes comprimentos do teto até o chão. “É possível utilizar os anéis para atravessar o espaço, o risco é todo seu. Somente duas pessoas são permitidas por vez. Obrigado”. The Fact of Matter faz com que o “espaço” se torne uma questão: ao ocupá-lo e ao propor sua ocupação. Que corpos poderiam surgir com o uso desses anéis? Que espaços? Corra seu risco. Descubra e compartilhe sua política.

Nos últimos anos, o coreógrafo William Forsythe vem pensando como dança e coreografia podem existir em outros contextos e mídias, como por exemplo no caso dos filmes e vídeos (Solo, Suspense, Antipodes I / II), das instalações City of Abstracts, Scattered Crowd e Defenders Part 2-3 / his film 1.2.3, do CD-Rom Improvisation Technologies e, mais recentemente, do admirável projeto Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, Reproduced, uma mídia disponível on-line fruto do trabalho de uma equipe multidisciplinar que desenvolveu visualizações gráficas e computacionais para a coreografia.

Segundo Forsythe, conforme escreveu em seu texto Choreographic Objects: “coreografia é, ao mesmo tempo, um termo curioso e enganoso. A palavra em si, como o processo que descreve, é alusiva, ágil e furiosamente indócil. Reduzir coreografia em uma única definição é não entender o mais crucial de seus mecanismos: o de resistir e transformar concepções prévias de sua própria definição. […] Coreografia/coreografar e dança/dançar são duas práticas distintas e muito diferentes. No caso da coreografia e da dança coincidirem, a coreografia frequentemente serve como um canal para o desejo da dança. Alguém poderia facilmente assumir que a substância do pensamento coreográfico reside exclusivamente no corpo. Mas, é possível para a coreografia gerar expressões autônomas de seus principais, um objeto coreográfico, sem o corpo?”

Essa foi uma das ideias discutidas durante o seminário público que ocorreu dentro da programação do evento Focus on Forsythe, promovido pelo Sadles Well’s, em abril de 2009, em Londres. O pesquisador Scott de LaHunta organizou e coordenou a discussão cujo título ajuda a pensar mais sobre o assunto, Objetos Coreográficos: Traços e Artefatos de Inteligência Física. Forsythe e seus colaboradores, entre eles Siobhan Davies, Wayne McGregor e Emio Greco, conversaram sobre o conceito de objeto coreográfico e como ele virou realidade no projeto digital acima mencionado, o Synchronous Objects. Boa parte do debate girou em torno da exploração das tecnologias interativas digitais para documentar, representar, transmitir e disseminar importantes aspectos dessa prática artística. As várias fontes informacionais constituem objetos que o projeto investiga através de perguntas como: o que os dançarinos sabem? Como esse conhecimento pode ser capturado, transformado e acessado em outros campos de estudo além da dança? O que tem sido reconhecido como produção de conhecimento nesse fazer e que tipos de objetos podem ser tomados como conhecimento para outras disciplinas?

Questões como essas estarão em pauta nos próximos anos, desafiando profissionais de diferentes especialidades a trabalharem juntos em projetos que situem a produção de conhecimento da/em dança e promovam adiante a sua compreensão/documentação/visualização.

Por fim, ainda dentro da programação da Bienale di Venezia, vale conferir as instalações dos brasileiros Lygia Pape e Cildo Meireles, as obras do espanhol Miquel Barceló (inclusive o vídeo de uma de suas perfomances), a sala do chileno Iván Navarro, as esculturas de palha de Ahmad Askalany… Perca o dia (ou dias) lá dentro. Os amantes das artes do corpo precisam checar também o pavilhão do artista Jan Fabre com a exposição From the Feet to the Brain, curada por Linda e Guy Pieters, em Arsenale Novissimo. Confirme antes, pois tem dias em que o pavilhão está fechado, mas você só fica sabendo disso quando está na frente dele.

Maíra Spanghero é pós-doutoranda, com suporte da CAPES, na Brunel University, em Londres, onde pesquisa a relação entre dança e matemática na obra dos coreógrafos William Forsythe e Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

What brought me to Veneza wasn´t exactly the allure of one of the most beautiful (and tourist attracting) cities in the world, even tough the desire to visit it had existed for a long time. Also, it was not exactly the company of friends who made my stay joyful. Neither was it the European summer vacations. That which really motivated my trip was the premiere of the work of choreographer William Forsythe (1949), The Fact of Matter, which was part of the 53rd 53a Bienale di Venezia running from June 7 to November 22, 2009. The biennial is a huge undertaking and everything breathes arts on the streets, museums, galleries, churches, boats, people. The city itself can be considered an outdoor museum as it was founded in the year 950, it carries a long history that went through its favorable and strategic geographic position between the West and the East. Nothing could be more appropriate than naming the airport after merchant and explorer Marco Polo, right?

Before I bought the tickets for the exhibition (they cost 18 euro and give access to two areas where the event spreads out, in Arsenale and Girardini), I checked some information at the website of Forsythe’s company, The Forsythe Company. If you do the same, you´ll realize there is only one “ page” with information restricted to the name of the piece, its author, the year of the premiere, the dates, the promoters/producers and the word “tickets” that linked to the URL of the famous biennial’s website. With about 90 artists, it wouldn´t be hard to find the name of the choreographer if the search engine of the website worked. The result is nothing. The event’s publication brings a list of participants in alphabetic order but Forsythe’s name is not there. Nothing on the leaflets and the ushers also couldn´t inform anything.

Was I facing a detective investigation?

Since there was no information available, I started to think that maybe the installation had been cancelled for some reason and something was virtually outdated. With all this confusion, the size of the exhibition and the amount of works, how was I to find William Forsythe’s new piece, in case it was actually there?

I had no alternative but to go there personally. So it was on my third visit, totally by chance, that I found the The Fact of Matter! Soon after being fortunately taken by surprise by the sculptures of American artist Miranda July, while I was strolling through the garden, in Arsenale. The place is a mix of lawn, woods, stones, birds and other animals surrounded by an industrial and port landscape with 16th century architecture. The Fact of Matter is virtually hidden in a more reserved part of this area. You only suspect there´s something related to the exhibition because you can see from afar the paper display with the credits of the pieces, in the Bienale pattern.

The room of his most recent choreographic object, as Forsythe has been calling some of his works, is an apparently abandoned place and not very big. The two openings are covered with vegetation There´s rust and dust. If you don´t care to read the credits with the “explanation” placed at the entry, inside the place you´ll be surprised by 200 gymnastics rings hanging at different lengths, from the ceiling to the floor. “It´s possible to use the rings to cross the space, the risk is all yours. Only two people are allowed at a time. Thank you”. The Fact of Matter turns the “space” into an issue: by occupying it and proposing its occupation. Which bodies could emerge from the use of the rings? Which spaces? Take the risk. Find out and share your policy.

In the last years, choreographer William Forsythe was been thinking about how dance and choreography can exist in other contexts and media, like, for example, in the case of films and videos (Solo, Suspense, Antipodes I / II), the installations City of Abstracts, Scattered Crowd and Defenders Part 2-3 / his film 1.2.3, the CD-Rom Improvisation Technologies and most recently the striking project Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, Reproduced, a media available online, the result of the work of a multidisciplinary team that developed graphic and computer visualization for the choreography.

According to Forsythe, as he wrote in his text Choreographic Objects: “Choreography is a curious and deceptive term. The word itself, like the processes it describes, is elusive, agile, and maddeningly unmanageable. To reduce choreography to a single definition is not to understand the most crucial of its mechanisms: to resist and reform previous conceptions of its definition.[…] Choreography and dancing are two distinct and very different practices. In the case that choreography and dance coincide, choreography often serves as a channel for the desire to dance. One could easily assume that the substance of choreographic thought resided exclusively in the body. But is it possible for choreography to generate autonomous expressions of its principles, a choreographic object, without the body?”

This was one of the ideas discussed during the public seminar that took place within the program of the Focus on Forsythe event, in April 2009, in London. Researcher Scott de LaHunta organized and coordinated the debate whose title helps to think more about the subject, Choreographic Objects: traces and artifacts of physical intelligence . Forsythe and his collaborators – Siobhan Davies, Wayne McGregor and Emio Greco – talked about the concept of choreographic object and how it became reality in the digital project mentioned above, Synchronous Objects. Most of the debate revolved around the exploration of digital interactive technologies to document, represent, convey and spread important aspects of this artistic practice. The many informational sources make up objects the project investigates through questions like: what do the dancers know? How can this knowledge be captured, transformed and accessed in other fields of study other than dance? What has been recognized as knowledge production in this practice and what types of objects can be taken as knowledge to other disciplines?

Issues like that will be in the agenda over the next years, defying professionals from different specialties to work together in projects that locate the knowledge production of/in dance and further promote its understanding/documentation/visualization.

Finally, still within the Bienale de Venezia program, it´s worth checking out the installations of Brazilian artists Lygia Pape and Cildo Meireles, the work of Spanish artist Miquel Barceló (including the video of one of his performances), the room of Chilean Iván Navarro, the straw sculptures of Ahmad Askalany… spend the day (or days) in there. The lovers of the arts of the body must also check out the Jan Fabre’s pavilion with the exhibition From the Feet to the Brain, curated by Linda and Guy Pieters, in Arsenale Novissimo. Confirm first, because some days the pavilion is closed but you only find out when standing in front of it.

Maíra Spanghero is post-doctorate candidate at Brunel University, in London, where she is researching the relationship between dance and mathematics in the work of choroegraphers William Forsythe and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.