O corpo situado & O cérebro da dança | The situated body & The dancing brain

Dois trabalhos, um deles publicado muito recentemente (junho de 2008), merecem especial atenção dos leitores do idança. Eles são THE SITUATED BODY, que é uma coletânea de artigos editados por Shaun Gallagher, para o peródico Janus Head, e SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE? que é um artigo de divulgação publicado na Scientific American Magazine.

Vou começar comentando rapidamente o primeiro.

Em um cenário muito diferente daquilo que é conhecido como teoria computacional da mente, ou TCM, a cognição NÃO é um fenômeno desencorporado, resulta de pressões evolutivas, NÃO é predominantemente consciente, é ‘engajada’ emocionalmente e é radicalmente dependente do ambiente (cultural, social e físico) em que está imerso. (em termos sumários, a TCM afirma que a mente atua como uma máquina que seleciona, estoca e manipula representações de acordo com procedimentos sintáticos ou algorítmicos) Fala-se cada vez mais em cognição contextualizada e situada, mente embebida e corporificada (situated, embodied and embedded mind).

A cognição é descrita como o espaço onde estão densamente acoplados o corpo, o ambiente (físico e cultural) e o cérebro. Cientistas e filósofos vêem aí um projeto de reconcepção radical do homem, em que são colocados em xeque, de uma só vez: a imagem de uma mente encapsulada em um cérebro; a concepção de criaturas biológicas complexas como processadores de informação; a concepção de informação como uma entidade bem estruturada, fornecida por um ‘mundo pronto de problemas’; o papel das representações mentais, simbólicas, em processos cognitivos. A quem chame o resultado de ‘homem pós-cartesiano’. Alguns dos precursores históricos incluem de Hyle a Ponty, de Bergson e Heiddeger a Hupert Dreyfus, de Charles Peirce, William James e Jacob von Uexkull a James Gibson.

As idéias que nutrem este ‘novo paradigma’ com pressupostos e resultados têm consequências em muitas áreas – ciência cognitiva, etologia, robótica, psicologia, neurociência, linguística, semiótica, educação, fenomenologia, artes. Mais ou menos recentemente, o jornal Janus Head (9/2/2007) publicou um número especial dedicado ao tema COGNIÇÃO SITUADA com diversos artigos sobre arte, dança, performing arts. Nele são tratados muitos tópicos: como processos dependentes de contextos afetam a cognição? Como o agente, localmente embebido em circunstâncias diversas, é capaz de atuações muito diferentes com respeito à ‘mesma’ atividade cognitiva? Como o corpo, estendido no ambiente estruturado por linguagem, e outras próteses tecnológicas, tem alterada suas competências?

O leitor encontrará o corpo como ‘campo’, ‘laboratório’, ‘objeto’ de diversas experiências, triviais, situadas e estéticas, encontrará uma visão metafísica de subjetividade submetida a uma revisão, um tratamento sobre o papel da propriocepção na constituição do self fenomenológico, um tratamento da dimensão afetiva do movimento, em termos filogenéticos, ‘para evitar a dor’ e aumentar o prazer, uma reconsideração do papel do ambiente e do contexto em tarefas e atividades criativas… O leitor vai encontrar, neste número especial, linhas gerais de uma teoria da arte empiricamente responsável, comprometida com uma epistemologia evolutiva, científica, e ao mesmo tempo, avessa a um reducionismo neurobiológico prestigioso em diversos campos.

Sobre o outro artigo — ‘In dance, spatial cognition is primarily kinesthetic’. O leitor do artigo SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE? encontrará esta e outras afirmações (por exemplo: ‘Dance is a fundamental form of human expression that likely evolved together with music as a way of generating rhythm’) além de perguntas: como dançarinos navegam no espaço? Como estão relacionados dança e linguagem? Que mecanismos neurais atuam no controle de complexas atividades motoras? Como estão relacionados imitação e aprendizagem motora?

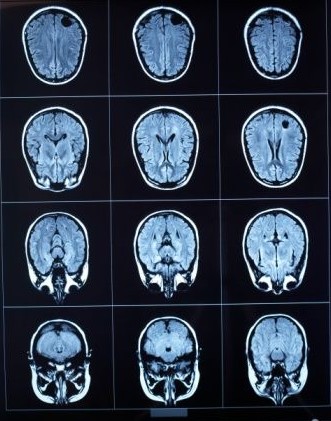

O artigo resume o que pode ser considerado o conjunto mais interessante de resultados produzidos sobre dança e técnicas de imageamento funcional do cérebro. Através destas técnicas pode-se mapear com precisão espaço-temporal regiões cuja ativação indicam aumento de processamento em circuitos especializados do cérebro. A arquitetura dinâmica de ativação de regiões envolvidas em muitas tarefas cognitivas, por exemplo, produção de linguagem, inferências, emoção etc, são relativamente bem conhecidas. Este não é o caso da dança, ou do ‘cérebro da dança’. O artigo descreve as vias de propagação de informação, do córtex parietal posterior aos músculos requeridos às atividades motoras, e de volta, através de feedback, ao córtex. Alguns dos problemas mais interessantes são os mecanismos neurais envolvidos na execução de movimentos complexos (e ‘graceful‘). Outros problemas envolvem a história evolutiva deste traço ou comportamento. Por que teria surgido a dança? O artigo sugere, mas não explora, a idéia de que a dança pode ter surgido como uma forma de proto-linguagem, já que complexos movimentos ativam áreas homólogas à área de Broca, associada a produção da fala.

Há, ao longo do artigo, muitas sugestões. Por exemplo, mecanismos de imitação, relacionados a ‘aprendizagem social’, são cruciais ao surgimento da dança e são dependentes de estruturas neurais conhecidas como ‘neurônios espelhos’.

Minha sugestão é que se examine com cuidado os resultados deste grupo de pesquisa, e grupos associados mencionados. Há, em ambientes maduros, disputa entre ‘predomínios’ exercidos por diferentes ‘níveis de organização’ dos fenômenos investigados, em termos explicativos (físico, biológico, psicológico, histórico, cultural etc), para não falar de disputas internas, i.e., no ‘interior’ dos níveis, entre teorias, métodos e modelos. As disputas devem ser proveitosas, se não tenderem à muita polarização. Os resultados divulgados no artigo introduzem o que é ainda uma novidade, em termos de história da ciência, ou de história das idéias, nos estudos sobre dança. As considerações sobre as bases neurobiológicas de diversas atividades cognitivas-estéticas, em música, artes visuais, literatura, etc, são uma tendência pronunciada. Os estudos sobre dança devem começar a se beneficiar desta tendência.

João Queiroz é diretor do Group for Research in Artificial Cognition (UFBA/ UEFS)

Two papers deserve special attention from the readers of idança: THE SITUATED BODY, a collection of articles edited by Shaun Gallagher for the Janus Head journal; and SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE, an article published in the Scientific American Magazine.

I´ll begin by briefly commenting the first one.

In a very different scenario from what is known as computational theory of the mind, or CMT, cognition is NOT a disembodied phenomenon, results from evolutionary pressures, is NOT predominantly conscious, is emotionally ‘engaged’ and is radically dependant on the environment (cultural, social and physical) in which one is immersed. (In brief terms, CMT asserts the mind acts as a machine that selects, stores and manipulates representations according to synthetic and algorithmic procedures). Contextualized cognition and situated, embodied and embedded mind are more and more discussed.

Cognition is described as a space where the body, the (physical and cultural) environment and the brain are densely connected. There, scientists and philosophers see a project of radical reconception of man, in which all at once the following are put to test: the image of a mind encapsulated within a brain; the image of complex biological creatures as information processors; the concept of information as a well structured entity, offered by a ‘fixed and structured world of problems’; the role of mental, symbolic representations in cognitive processes. There are some who name the result as ‘post-cartesian man’. Some of the historical precursor include from Hyle to Ponty, Bergson and Heidegger to Hupert Dreyfus, from Charles Pierce, William James and Jacob von Uexkull to James Gibson.

The ideas that nourish this ‘new paradigm’ with presuppositions and results have consequences in many areas – cognitive science, ethology, robotics, psychology, semiotics, education, phenomenology, art. Somewhat recently, the Janus Head journal published a special number dedicated to the subject of SITUATED COGNITION with many articles about art, dance, performing arts. Many topics are dealt with: how does processes dependent on context affect cognition? How is the agent, locally embedded in diverse circumstances, capable of many different actions relating to the ‘same’ cognitive activity? How does the body, extended in an environment structured by language and other technologic prosthesis, have its abilities altered?

The reader will find the body as ‘field’, ‘laboratory’, ‘object’ of diverse experiences, trivial, situated and aesthetic, the reader will also find a metaphysical view of subjectivity submitted to revision, a treatment about the role of proprioception in the constitution of the phenomenological self, a treatment of the emotional dimension of movement ‘to avoid pain’ and increase pleasure, a reconsideration of the role of the environment and the context in creative tasks and activities… The reader will find in this special number general lines of a theory of art empirically responsible, committed to an evolutionary, scientific epistemology, and at the same time, contrary to a neurobiological reductionism prestigious in many fields.

About the other article – ‘In dance, spatial cognition is primarily kinesthetic’. The reader of the article SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE? will find those and other assertion (for instance: ‘Dance is a fundamental form of human expression that likely evolved together with music as a way of generating rhythm’) besides the following questions: how do dancers navigate in space? How are dance and language related? Which neural mechanisms act in the control of motor activity?

The article summarizes what can be considered the most interesting set of results produced about dance and functional brain imaging techniques. Through these techniques it is possible to precisely map with space-time precision regions, which activation indicate an increase of processing in specialized circuits of the brain. The dynamic activation architecture of regions involved in many cognitive tasks, the production of language, inferences, emotion, etc, for example, are relatively well known. It is not the case of dance, or the ‘dance brain’. The article describes the propagation paths of information, from the posterior parietal cortex to the muscles required in motor activity and back to the cortex, through feedback. Some of the most interesting problems are the neural mechanisms involved in the execution of complex and graceful movements. Other problems involve the evolutionary history of this trace or behavior. Why was dance born? The article suggest, but does not explore, the idea that dance may have emerged as a form of proto-language, since complex movements activate areas homologous to Broca’s area, associated to speech production.

Through the article there are many suggestions. For example, the imitation mechanisms, related to ‘social learning’, are crucial to the appearance of dance and depend on neural structures known as ‘mirror neurons’.

My suggestion is that the results of this set of research and the associated groups mentioned above should be carefully examined. In mature environments there are disputes between ‘predominances’ carried out by different ‘levels of organization’ of the investigated phenomenon in explanatory terms (physical, biological, psychological, historical, cultural, etc), not to mention internal disputes, i.e. in the ‘inside’ of levels, among theories, methods and patterns. The disputes should be rewarding, if they do not tend to much polarization. The results published in the article introduce what is still new, in terms of science history, or the history of ideas, in the study of dance. The considerations about the neurological basis of many cognitive-aesthetic activities, in music, visual arts, literature, etc, are an accentuated tendency. Studies about dance should start to benefit from this tendency.